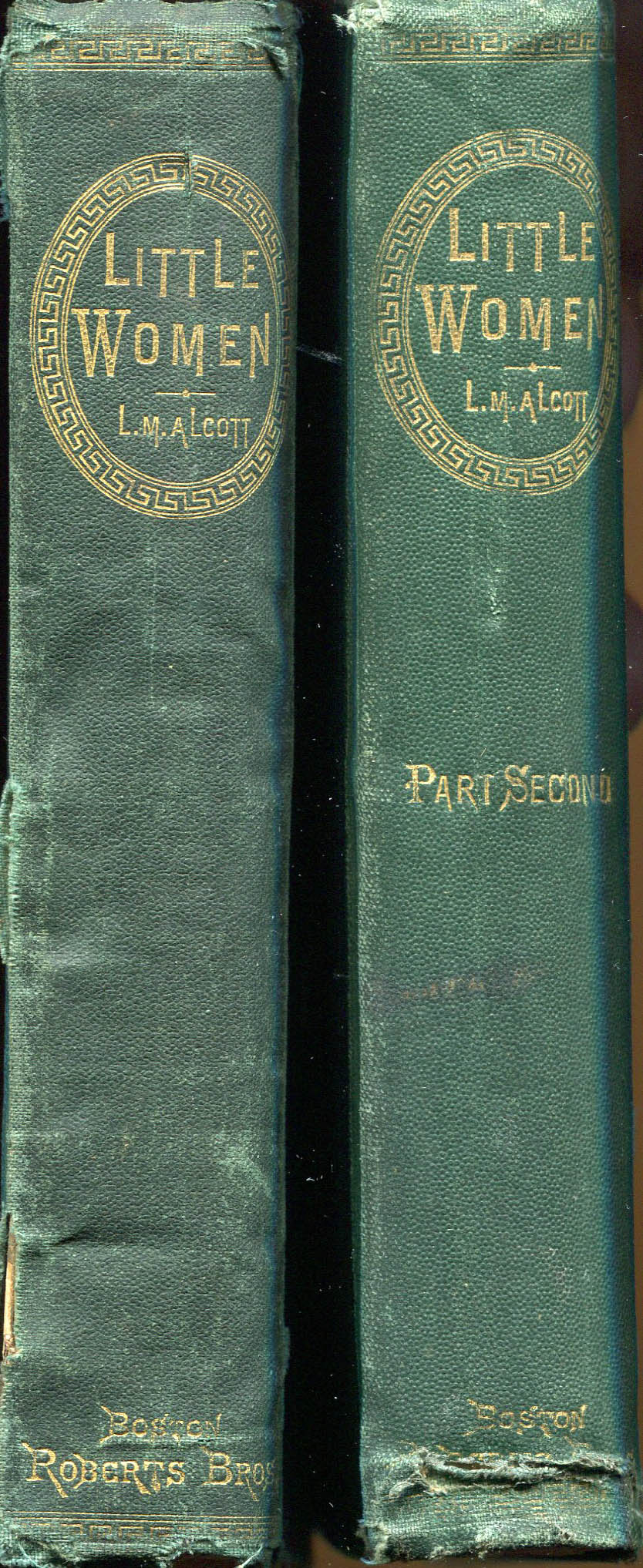

Elsewhere someone speaks about Louisa May Alcott's

Little Women and women as artists, after re-reading the book for the first time since she was thirteen. Which got me thinking again about Alcott -- who enters my thoughts constantly and has since I was nine, and first read Little

Women and

Little Men. Both those were on the shelves at home. It wasn't until three years later that I was in a school that had her other books in the library.

What I have taken away from so many re-readings of all of Alcott's books that they are memorized is that she believes the artist will spring up in any family at any time no matter what class the family. Talent should be nurtured and hopefully guided into the paths that will best express the talent, while owner is taught to be decent person -- while always taking into account talent might not be 'enough.' Nor is one to believe that artistic talent in a woman or a man makes them superior to the talent that it takes to create a home and nurturing environment for their families.

Family is central. However, as the family is central to a woman, so it is to the father -- and so, with a man's, is women's place in the larger community and the world. Women have as much a role to play in the world outside the home as do men, and a duty to do so.

At the end of life filled with toil and sorrows, it was just Louisa and her father Bronson living, 'all in all to each other,' as is described the care Jo March provides for her dying sister, Beth in Little Women. Daughter and father died within days of each other, she going first. Bronson Alcott's grief was inexpressible.

The books that brought Alcott fame and fortune were all written subsequent to the Civil War, which they ardently supported. The Alcott family was intimately connected to the intellectual and social circles of Boston for whom Abolition was an article of faith from before Louisa was born -- along with advocacy of many other conditions, such as prison reform.

Louisa Alcott herself lived everything that she endorsed, including the Civil War, fought in order to abolish slavery from the United States. She mutes her advocacy about the subject of the Civil War in her novels, yet it is always there. Alcott herself nearly died after nursing wounded soldiers in a D.C. hospital. She wrote her "Hospital Sketches," her first seriously noticed work from letters she sent home during that time. She also wrote other anti-slavery essays and poems before and during that period. Earlier, her father lost a school for bringing in a small black child to be educated with the white students. Not even abolitionist Boston would put up with that. This was a great difference between the Alcott family, as led by Bronson, and almost every one else: they stood for full integration, along with the 'radical' abolitionists such as Thaddeus Stevens.

The first time I learned of the Civil War in fact, was from Alcott. The opening page of

Little Women refers to the absent father, "far off, where the fighting was." When the father becomes ill later in the book and is sent to a D.C. hospital, Jo March wants wildly to go there and nurse him. In

Little Men, old Silas, the black man of all work at Plumfield, tells the children the story of his heroic, beloved horse, shot out under him in a battle, while he himself is gravely wounded, next to another dying, enemy soldier. Though not a word is said about this, Silas would have been either a free black man who enlisted in the black regiment out of Massachusetts and Connecticut, or a contraband slave, who then enlisted in the Union army. Growing up on a farm in a state that didn't even exist when the Civil War was fought, it wasn't a constant from birth as it was for my Southern-born el V. I didn't hear of the Civil War in school until the fourth grade. (Also, though it was a time in which the Civil War centennial was going on, in which slavery was left out of the official observances entirely, in our schools we were taught the war was fought "to free the slaves.")

Elsewhere someone speaks of re-reading

Little Women for the first time since she was thirteen, when she hated the book because she thought the writer character was denied her right to be an artist. She sees the book rather differently and wonders if Alcott continues this dialogue about women and artists. All of her books do this in some way or another. Alcott speaks directly, straight up, in some of the chapters of the second volume of

An Old Fashioned Girl about women practicing art, and the never-yet-resolved conflict for women between the domestic sphere and the practicing artist.

Nor does she leave not notice that this is a dilemma for boys and men too.

Under the Lilacs provides a rather odd arc of the lost boy circus equine acrobat tale, who shows up at the start of

Under the Lilacs one day and is taken in by the family to whom the lilacs belong. Unlike the March family, this one is a modest rural family, and are not connected to the great intellectual, political and social currents of the day, but are decent, self-sufficient people, who do their best for others, while making their own way. He has to give up that kind of exhibition in order to grow up -- in order to not be an orphan, to become a useful part of the community. He does a farewell appearance, which is heart-tugging, even though he's willing -- he knows as well as the Mother that in a few months he'll be too big to do his tricks.

In

Eight Cousins and the sequel

Rose in Bloom, there is not interest in being an artist one's self -- as there are all through the March family chronicles -- among the upper crust, wealthy family members and their social circle who feature in these two books. However, in the first novel there is Phoebe, a kitchen girl, who can sing extraordinarily well. She is befriended by the lonely, newly orphaned Rose. Over the course of the book Rose learns lessons from Phoebe, in patience, resolve, carrying one's burdens with a cheerful, willing heart. But, by the opening of

Rose in Bloom, Rose's uncle-guardian had subsidized Phoebe's professional vocal training, as her voice is worthy of that nurture. Phoebe has embarked on an authentic career as soloist. In this second book, Mac, another of Rose's cousins becomes a celebrated poet -- going against the family's expectations for him in the first book -- but he's also gotten qualified as a physician. At one point Rose frets that she's just a stay-at-home, not famous and celebrated like Phoebe and Mac. With her uncle-guardian's guidance she understands that what she does is equally valuable. In the meantime Phoebe and Archie, the oldest of the male cousins, fall in love -- to the dismay, displeasure and prohibition of the aunts. "No one knows who she is!" In the end, it isn't Phoebe's talent or success in exercising it, but that she, along with the doctor-poet Mac, nurse Rose's uncle to health during a life-threatening illness, that gets her accepted by the aunts. Now Phoebe's will give up her career -- and sing only for the expected babies. Yet it was the very wildness and sound of Phoebe's voice, at least as much as her sparkling black eyes, that attract Archie into love. There's also a very very very subtle hint that Phoebe may have some 'black' blood ... the Alcotts were nothing if not abolitionists first, and after the war, integrationists.

In

Jo's Boys, the final March family chronicle, Josie, Meg's daughter, Jo's niece, is mad to go on the stage (as was Jo March when young -- she and her older sister Meg loved acting in their home theatricals. As the family is a respectable entity to themselves and their community, Josie's ambition is discouraged (actresses were still pretty much part-time prostitutes at the time, with few exceptions). Yet, in, the end, she gets permission to study, when a great actress watches her perform and declares Josie has what it takes -- though without any guarantees, of course. There is also the character of Nat, continued from

Little Men, whose love for the violin has also continued since Little Men. He's provided training, and then is subsidized to study in Europe. It is thought he has sufficient authentic talent enough to earn a decent living (which is nothing at all to sneer at -- the abilities necessary are many and not that many people possess them), but he's not a great musicians. In the meantime, Jo March has continued to write, and had begun to do so for money. Then it was to feed -- I loosely quote -- the "ravenous maws of the children who demanded, more, more, more."

Louisa Alcott always wrote for money even more than she did for expression -- she was so poor for most of her life. She wrote when she was ill, when the people she loved were dying and after they died. Alcott, as much as any of her female contemporaries this period -- equally, I feel, with George Eliot, who also was very poor for a very long time, and wrote for money as well as expression -- was in the situation to explore the varieties and levels of talent and how to express it as a woman. -- as well as the enormous and many obstacles against her doing so.

To bring us back to the Civil War, after it was over, and sometimes even before, hordes of southerners made their way north, particularly to New York City, to re-make their fortunes. They were called the Confederate Carpetbaggers. Many of them were writers and other professionals. Among them were many, many women, and many of them too turned to writing, to support their families. They wrote for the same reasons Louisa May Alcott did, and some of them with equal success.