"Art is no part of Southern life," he wrote. He described how it was different in New York and Chicago. The reason was simple: the latter two -- representing the East and the Middle West -- were young and vigorous, whereas the South was "old since dead ... killed by the Civil War." The "new South" was not Southern at all but merely a land of immigrants trying to remake the South along Northern lines. "Yet this art, which has no place in Southern life, is almost the sum total of the Southern artist. It is his breath, blood, flesh, all." He went on from there to the most conscious scrutiny of Southern writing he had ever attempted.

"Because it is himself the Southern is writing about, not about his environment; who has, figuratively speaking, taken the artist in him in one hand and his milieu in the other and thrust the one into the other like a clawing and spitting cat into a croker sack. And he writers. We have never got and probably will never get, anywhere with music * or the plastic forms. We need to talk, to tell, since oratory is our heritage. We seem to try in the single furious breathing (or writing) span of the individual to draw a savage indictment of the contemporary scene or to escape from it into a make-believe region of swords and magnolias and mockingbirds which perhaps never existed anywhere. Both of the courses are rooted in sentiment, perhaps the one who writes savagely and bitterly of hte incest in clayfloored cabins are [sic] the most sentimental. Anyway, each course is a matter of violent partizanship, in which the writer unconconsciously writes into every line and phrase his violent despairs and rages and frustrations or his violent prophesies [sic] of still more violent hopes. That cold intellect which can write with calm and complete detachment and gusto of its contemporary scene is not among us; I do not believe there lives the Southern writer who can say without lying that writing is any fun to him. Perhaps we do not want it to be."

|

| Residents of Lafayette County, out of which Faulkner imagined his Yoknapatawpha County |

Blotner, p. 831; February 1934; Faulkner letter to his publisher, Harrison (Hal) Smith:

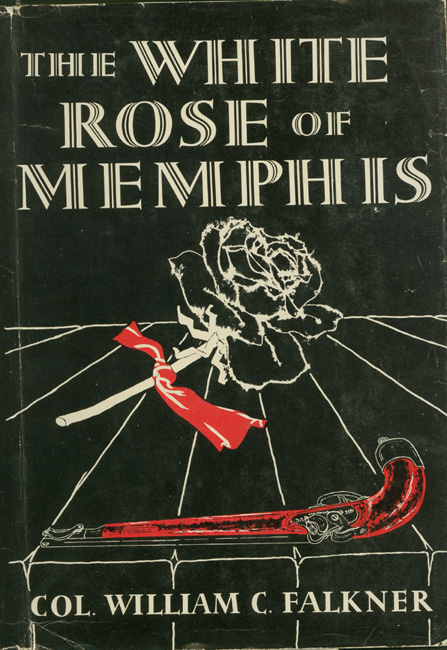

" .... "I believe that I have a head start on the novel," he began. "I have put both the Snopes and the Nun ** one aside. The one I am writing now will be called DARK HOUSE *** or something of that nature. It is the more or less violent breakup of a household or family from 1860 to about 1910. It is not as heavy as it sounds. The story is an anecdote which occurred during and right after the civil war; the climax is another anecdote which happened about 1910 **** and which explains the story. Roughly, the theme is a man who outraged the land, and the land then turned and destroyed the man's family. Quentin Compson, of the Sound & Fury [sic}, tells it, or ties it together; he is the protagonist so that it is not complete apocrypha. I use him because it is just before he is to commit suicide because of his sister, and I use his bitterness which he has projected on the south in the form of hatred of it and its people to get more out of the story itself than a historical novel would be. To keep the hoop skirts and plug hats out, you might say." *****In my mid-twenties I was fascinated by Faulkner's fiction. I read and re-read all the great American novelists with profound wonder and care. The Novel! it was my grande amor, to which I'd faithful to death and after! Slowly, fighting it every realization along the way, I gave into despair about these 20th century white male writers, because they depressed me with their unexamined presumptions about women. Faulkner, as much as Fitzgerald and Tennessee Williams is responsible for the crazy women who populate southern fiction. Then, to my terror, all fiction, with a few exceptions began to read increasingly repetitive, predictable, complacently stuck on adolescent matters, nay, even infantile obsessions.

Finally, in these days, slowly I’m creeping back into some of joy and admiration of fiction. It seems to have begun with Fitzgerald, and then Faulkner. Perhaps it's because I came to them more in terms of historical fiction (as with Faulkner) and in terms of history embedded in fiction (as with Fitzgerald). As well, since my mid-twenties – the South has become the center of my scholarship. Mastery of a variety narrative approaches is as essential for a writer of history as it is for a writer of fiction. It always pays to study the best.

Life takes you places you never expected, which perhaps is why we remain reluctant to leave it.

----------------------

* He evidently didn't think Jazz qualified as musical art, much less all the other forms of southern black music with which he was more than familiar, both in his home region and from the time he spent in speaks in Memphis and New York. He'd spent a lot of time in his youth dancing to W.C. Handy playing live, with his band, in Oxford. He attended a lot of dances, and by all accounts, if he wished to dance, he danced well. He was a musical person.

**

The Nun refers to Requiem for a Nun (1950) the sequel to Sanctuary (1931). It was in Requiem for a Nun Faulkner wrote what may be the most famous line of American literature, maybe even the requiem for the fate of the nation, as we repeat endlessly our cycles of psychic bigotry and violence, as well as the economic cycles of boom and bust: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” There are those who would argue that the most famous line in American Literature comes from Gone With the Wind, and will quarrel over which one that is, whether, "My dear I don't give a damn," or "I'll think about it tomorrow."

*** THE DARK HOUSE is what will become Absolom, Absolom! (1936).

**** 1910 is years after Faulkner was born (1897), which makes even more interesting he might think an historical novel is. One aspect of Faulkner's genius in terms of narrative capacity as a novelist was how he could sail around in his history. Characters and events in single works, in his short fiction as well as his novels, emerge out of a variety of temporal locations: before the Civil War, during the Civil War, and return to the present, i.e. the present in which he the author was putting these words on paper. This is not easy to do, particularly not with narratives as multiply populated as Faulkner's are. He groped intensively for years as how to accomplish this. It was the tools of modernist narrative, forms with which he grew up, in fertile collision with the local language and oral storytelling modes with which he also grew up, that made works such as The Sound and the Fury successful and enduring.

***** It’s interesting to see contemporary Mississippi novelist, Greg Illes, working in the post-Faulknerian south now, attempting to bring to light the non-dead past of the Civil Rights era sins, crimes and evil. These are the matters of a trilogy Illes is writing. The first volume, Natchez Burning, was published this year. The Bone Tree and Unwritten Laws will follow. As Natchez Burning's as protagonist, Penn Cage, is Mayor of Natchez, it seems likely the two sequels will also feature that center of true historical evil, Natchez. Judging by the material of the first installment this trilogy appears to follow the arc from the JFK assassination to that of Martin Luther King, or maybe Bobby Kennedy as well. The perpetrators are a coalition of the New Orleans – Miami mob and bigoted corporate interests, employing generationaly violent criminals, sharpshooting Mississippi lowlifes – “white trash”. Freedom Summer in Mississippi is the sort of material Illes may be working with.

What for me, at this time, is most interesting about Faulkner the man as well as his fictional world, is that, unlike Natchez, Yoknapatawpha County is not part of the Delta, center of Mississippi aristocracy past and present. This mattered very much to Faulkner, a part of his sense that most southern fiction was phony, and his determination to show the real South, through hisknowledge of his own country and people.