I remain puzzled that I hadn't previously made the connection from the self-revelations in Samuel Pepys's diaries detailing his highly profitable war profiteering in the King's service during the Dutch-English wars,

with the rise and fall in financial fortunes of Jane Austen's characters in the age of the Napoleonic wars. It was reading

The Love of Strangers that set off that connection -- in particular the bit about the architect who is a Pepys descendant.

p.52 of Nile Green's

The Love of Strangers: What Six Muslim Students Learned in Jane Austen's London (2016) --

... in 1809 an imposing town hall was completed on the High Street. . . . it was designed by the fashionable architect Samuel Pepys Cockerell (1754-1827). A surveyor to the East India Company and a descendant of the diarist Samuel Pepys, Cockerell was a leading player in the orientalizing fashions of the period.

|

| Sezincote House, Samuel Pepys Cockerell's most famous ediface |

Cockerell is direct proof of what it means to have an ancestor who got a place in a royal office. In Samuel Pepys's case it was the office charged with supplying the King's navy with 'victuals', hemp, lumber, sailors' slops -- and even more significantly, the office in charge of the accounts of taxes and borrowing of the funds to finance all the navy's needs. Samuel Pepys diaries document from the beginning of his landing this place, he take sharp and quick advantages of the many opportunities to collect 'presents' [bribes] from those anxious to get on the gravy train of contracts to service the needs of King and country.

Pepys starts small. His 'presents' are provided often as gifts of fine gloves to his wife, barrels of oysters, a silver mug. But as his abilities, devotion to the work -- especially the keeping of the accounts -- his shrewd, assiduous politicking, buttering up those above him, the good fortune that his social skills and company are excellent -- people generally like him

* -- he gathers power and influence with more important and lucrative matters put directly into his hands. By the 1660's he's no longer receiving appreciation of gloves and pork and dishes, but cash in larger and larger amounts. In the summer before the Great Fire, the sums are approaching 500 pounds. This in a time when an annual income of 30 - 50 pounds allowed a London middle-class family to live comfortably.

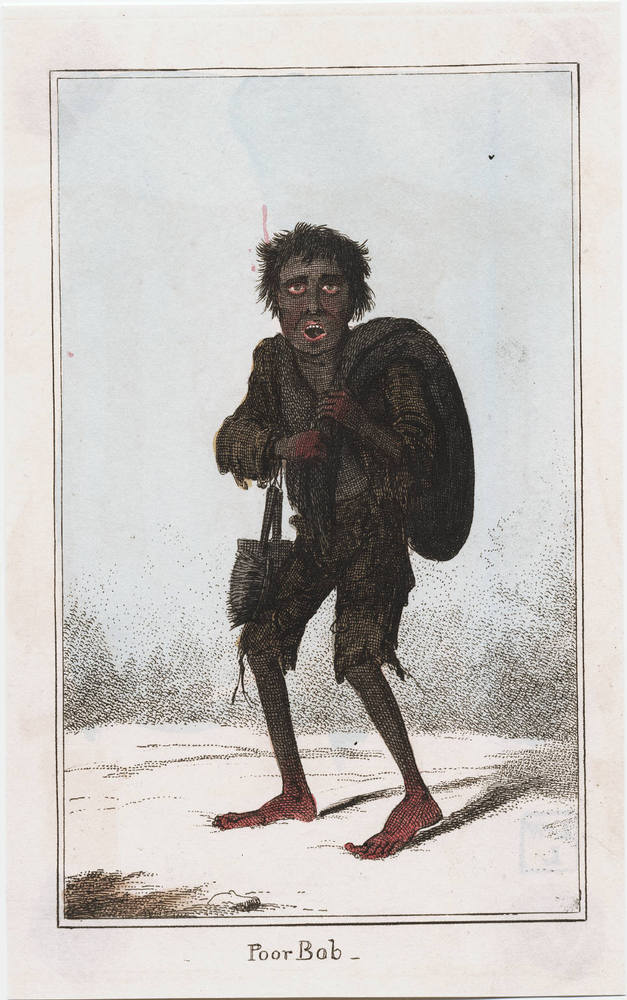

Pepys doesn't feel secure in his new wealth and position, though he enjoys it and wields it sharply to assist his family. In the 1666 summer the already-poor and less well-off are bearing the burden of manning and funding the badly handled Anglo-Dutch war. There's already been a long period of plague and many others have and / or are dying of famine. Every able-bodied man that can found is impressed on massive scale into the navy and army, further worsening the condition of already desperate women and children. Pepys is very frightened of a future he thinks he sees coming, particularly as the King and his slovenly, useless courtiers are perpetually broke, yet "pay no attention to business," and there's nothing with which to pay wages, finance the navy or run the war.

At times women riot about food. They also riot in protest of not being paid the impressment money they were to have for husband and son, or their husbands' back pay, which is months and months unpaid. Mobs pour into the naval office's the inner yard. Women, obviously starving, scream at him outside his office windows. He's also afraid Parliament, in reaction to the badly performing navy, will do him out of his position in the Navy commission. However, Pepys remains mostly happy and content, satisfied that he's acquired so much wealth that, as he and his wife discuss, they can retire to the country and buy an estate and establish themselves well if he loses his place in the naval office.

|

| Harlestone House, Northamptonshire, which has some of the elements of Mansfield Park's Mr. Rushworth's Sotherton Estate |

This is the template for a Bingley uncle, a Mrs. Elton's brother-in-law, Mr. Weston's purchase of a 'neat little estate', Emma's personal fortune of 30,000 pounds, Mr. Rushworth,

Mansfield Park's buffoon, engaged to Maria Bertram, who is so proud of his landscaping 'improvements'. Undoubtedly in the course of the creation of these picturesque landscapes he has displaced many working people and taken arable land out of cultivation.

** As well, in the course of these improvements either what had been a common resource of wood and stream was either destroyed or the access to has been removed for the small farmer and poor laborer.

Additionally this re-read for the first time in decades of Raymond Williams's Farnham chapter in his

The Country and the City, further pulled it together, particularly this page (110) quoting Cobbett:

[Williams] What was happening meanwhile to the landowners, and to their social structure, as rural capitalism extended? Cobbett looked very carefully at this, and made a familiar distinction between

[Cobbett] . . . a resident native gentry, attached to the soil, known to every farmer and labourer from his childhood, frequently mixing with them in those pursuits where all artificial distinctions are lost, practicing hospitality without ceremony, from habit and not on calculation; and a gentry, only now-and-then residing at all, having no relish for country-delights, foreign in their manners, distant and haughty in their behavior, looking to the soil only for its rents, viewing it as a mere object of speculation, unacquainted with its cultivators, despising them and their pursuits, and relying, for influence, not upon the good will of the vicinage [another term for geographical vicinity, neighborhood, community], but upon the dread of their power. The war and paper-system has brought in nabobs, negro-drivers, generals, admirals, governors, commissaries, contractors, pensioners, sinecurists, commissioners, loan-jobbers, lottery-dealers, bankers, stock-jobbers, not to mention the long and black list in gowns and three-tailed wigs [i.e. the legal professionals]. You can see but few good houses not in possession of one of the other of these. These with the parsons, are now the magistrates.

[Williams] . . . . What Cobbett does not ask is where the 'invaders' came from. Many of them, in fact were the younger sons of that same 'resident native gentry', who had gone out to these new ways of wealth, and were now coming back. Yet, 'native' or 'invade', the pressure on rents, and so through the tenant-farmer on the labourer, was visibly and dramatically increasing. Cobbett shortens the real time-scale, but then sees what is happening as agrarian capitalism extends. . . . .

Williams goes on to connect Cobbett's journalist's vision, his reporting of the country-side, and his advocating on their behalf, to the coming changes to the novel from the 18th century to what will begin emerging in the 1830's. The 1830's are when the novel begins to be the dominant literary form as well as that of popular entertainment. However, in the meantime:

[Williams] But this change in the novel did not happen in Cobbett's time. Through his middle years Jane Austen was writing from a very different point of view, from inside the houses that Cobbett was passing on the road. When he was writing about the disappearance of the small gentry he was riding through Hampshire, not far from Chawton. It was also in Hampshire he made his list of the new owners of country-houses and estates, from nabobs to stock-jobbers. We can find ourselves thinking of Jane Austen's fictional world, as he goes on to observe:

[Cobbett] The big, in order to save themselves from being 'swallowed up quick'. . . make use of their voices [the vote and their relatives and friends in Parliament and government] to get, through place, pension, or sinecure, something back from the taxes [for the wars with Napoleon, including paying Russian and others not to ally with Emperor.] Others of them fall in love with the daughters and widows of paper-money people, big brewers, and the like; sometimes their daughters fall in love with the paper-money people's sons, or the fathers of those sons . . . . But the small gentry have no resource.

Nor do the wage labourers and agriculture labourers have the privilege of the vote, friends and relatives in places of influence or any other resource to pressure those who are oppressing them. So they starve at the sides of the roads running past these great estates.

How thoroughly Austen's novels expose the historic political and economic purpose of marriage as survival and increase or loss of influence and wealth!

The more complete our understanding of that world broadens of which she forged her fictions the better we understand how the same factors of wealth, power, influence and politics are in play in our own times.

***

Which is one of the aspects that make great works of art endure, yes?

----------------------

* On the other hand. the more time I spend with Pepys, the less charming he becomes. It's not even his profiteering and infidelity -- it's his sexual abuse in particular that spoils his authentic family loyalty, his joy in music and the arts in general, his curiosity to learn as much about everything in the scientific and technological realms, his genuine hard work and general honesty with the King's property. The turning point came during one of those riots of starving London women needing their husbands' back pay -- they are all gotten away through force of arms. However, the prettiest one, he holds back and brings into his office. He gives her money, dismisses her, and swiftly follows in a his coach, picks her up and takes her where they can eff. He does this with other desperate women too, exchanging assistance for sex. He even does so with his wife's maid while his wife is in the house. Nor, of course by the rules of the time's engagement for prosperous men, can she object. This doesn't occur to him.

He lecherously speculates about every black' woman he encounters, no matter how virtuous, just assuming she would be willing to accomodate his sexual curiosity, if the opportunity should arise. (Evidently no opportunity to prove him right or false arises.) He's also an awful hypocrite, preying sexually on every woman who he can buy or persuade, but furiously anxious that some man will have designs on his wife.

** The very kind of opportunities for creating family webs of generationally aggregating wealth and influence deliberately denied to antebellum slaves by the conditions of the slave-breeding economy and slave selling economy. The bottom line of both depended first upon the perpetual, systematic shredding of the African American family. African Americans have not yet been able to catch up, thanks to the legally embedded racial system of ongoing oppression and repression and various sorts of exploitation that still, as a class, plunders their wealth the economic benefit of others.

*** The most desirable marriagable women seeking the best prospects don't have debut balls or Almack's (though they may, and some do, and these balls are becoming more common again), but compete to get into Harvard and go to ski resorts in Vail on vacation. See current studies that documentexogamic marriage has become increasingly rare, in terms of changing class, with the rise of private education in the pre-unversity years and the soaring costs of both. More than ever, for those already in the families of wealth and influence, practice endogamy. For awhile, in the first half of the 20th century this had changed with the massive influx of young women of all classes and background working in business offices of companies and institutions, where often romance blossomed with a young man with prospect or already established. U.S. movie romcoms particularly glorified this, in the 30's 40's and 50's.

Which makes the reader understand that in terms of the country and city, Jane Bennett and Elizabeth Bennett would never have been able to meet Bingley and Darcy unless they showed up in their less populated (i.e no wealthy rivals) and less formal vicinage. In other words, it would be highly unlikely their paths would have crossed in London -- and the competition by more prosperous and better connected women to secure their attentions would have been fierce.

Even more unlikely it would be that Elizabeth might have encountered Darcy in the more relaxed sociability of Bath, as who can imagine Darcy in Bath?