I listened to some Spinney interviews last year, though I haven't read the book -- I do have the flu currently, alas. (Yes -- I got the flu shot, back at the start of September, but we know this year was iffy for protection against the Big Mutator.)

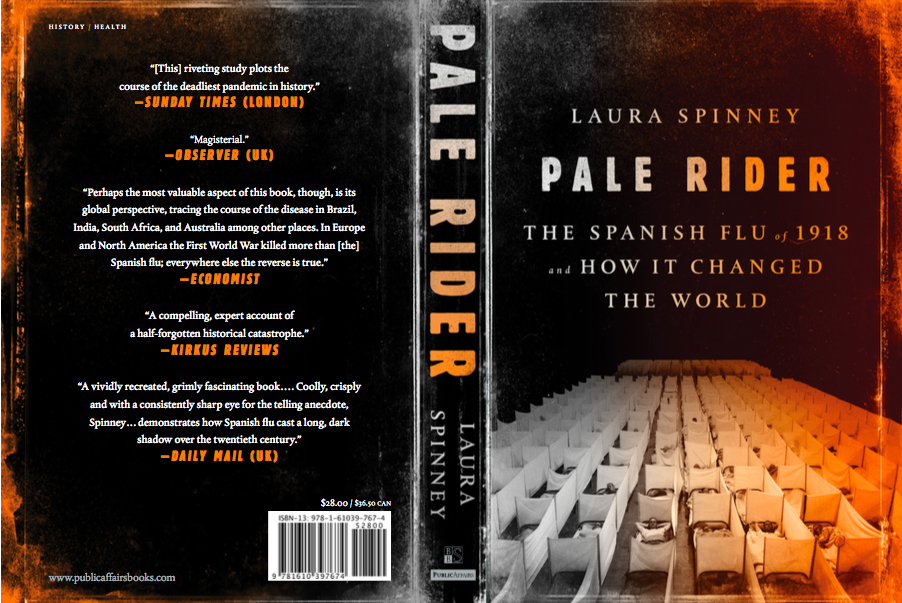

With the current flu getting so much news coverage one does think of this book, as well as because this is the centenary of the Spanish flu pandemic.

I learned from the review, (written by a physician) the three centers from which its global spread probably issued. I didn't know any of this before.

Maybe for me the most interesting factoid I got though -- is that perhaps the first flu epidemic was in 'Asia' 2000 years ago, acquired from horses. Was this the first strike against the rest of humanity by the Eurasian steppes and the nomads. long before the Mongols?

|

| Baiju Noyan is a bad man, a VERY bad man. |

I think of such a thing since I am watching the second season of Resurrection: Ertugrul, in which the big bad is the Mongols, and particularly Ogedei's general, Baiju Noyan.

Unlike in Jack Weatherford's histories of the Mongols, they are really eviLe here (though Weatherford pulls no punches when it comes to Genghis's sons, whom he holds responsible for what the Mongols came known for). They are worse by far than the first season's Crusaders. Even the nomad tent and their warriors (alps) say this is so. Certainly more prone to random acts of cruelty and torture for the sake of it, and bloody on a grand scale. This season is more graphically violent and grisly than the second one, which is only one large difference between the series' season 1 and season 2.

Initially, with the first episodes, I thought the second season was going to retell the first one, merely shifting roles around as to antagonists and protagonists and maybe even recreating the same characters but with different names and tribal membership.

But once I'd gotten a few episodes in, it was clear this season was very different. The poetry and passion of romance have almost disappeared. Halime Hatun, Ertugrul's love, to whom he now is married, is pregnant -- the longest pregnancy ever -- but she hardly ever appears except for him to order her "to be patient and wait." (I fear tremendously the Big Bad is going to kidnap her.) Mother Hayme seems to have lost her great wisdom just when she needed it most -- but plausibly so.

This season is far less concentrated on God's will, and the gorgeous mysticism and maybe, even the magic, of Islam. (However, we have a hermit who appears whenever Ertugrul is in the direst of straits, feeds him, hides him his cave, reunites him with his loyal alps -- some are traitors). Other annoyances of the first season, such as the predictable episode arc of at least one exceedingly lengthy battle scene, and the truly annoying predictable slo-mo, stop action, of horses galloping, have been dropped. Each episode moves faster than in the first season, and seem shorter though they are the same length.

Season 2's Ertugrul (called "Brave Man") is focused in utter desperation on keeping the promised arrival of the Golden Horde from overrunning all of Anatolia -- and perhaps, though much of this is vague, particularly in terms of the years involved, the Persian Seljuk Anatolian Sultanate of Rûm (Rome, i.e Byzantium, though that word wasn't used until the 16th century, while Istanbul didn't come into use until 1923), which borders the lands of Byzantium.

Along with this comes something I really like, the often overlooked aspect of the Mongolian generals' front line operations in the lands they are targeting for conquest. It didn't happen in one sudden, massive invasion.

Cohorts were sent ahead long before the arrival of the Golden or the Blue Hordes -- sometimes years. Not only did they perform terrorist lightning strikes along the borders and penetrate deeply into the targeted territory. They spent years subverting tribal influencers with bribery, kidnapping of family members controlling and using them behind the scenes.

Yet another aspect was to disrupt the local economies of trade, herding and manufacture (this is in the charge of women) as much as possible. As Baiju Noyan says, "The only thing I love more than fighting is winning a battle without having to fight it."

However, the Turkmen Seljuks employed the same tactics themselves when moving out of Central Asia into Asia Minor, with the same devastating effects upon the population and trade as the Mongols accomplished.

|

| Battle of Köse Dağ; Mongols won, Seljuks lost. |

From this I'm picking up that even today the Turks harbor no forgiveness for the Mongols, recalling with hatred their subjection of over a century, which happened after getting clobbered at the battle of Köse Dağ (1243) -- won, not coincidentally one might think, by -- Baiju Noyan.

Seemingly (I don't know -- my ignorance is abysmal) this subjection of the 300 year Seljuk Empire in Anatolia by the Mongols until their own empire fell apart is the reason there aren't histories of the Anatolian Seljuks per se as there are of other Seljuk spheres as in Persia, or the Arab eras, etc.

Additionally, Anatolia was where the

"The Mongols and the "Franks" [including the Venetians] made many alliances against the Egyptian Mamluks, the wall against which Mongols and Europeans always broke. Also Frankish-Mongol alliances weren't very effective to start with. The Mongols, i.e. the Ilkhanate Empire [see above] were allied with Byzantium -- though that also broke down constantly as well. Despite many attempts, neither Hulagu [brother of Kublai; ruler of the Ilkhanate Empire, including most if not all of Anatolia] nor his successors were able to form an alliance with Europe, although Mongol culture in the West was in vogue in the 13th century. Many new-born children in Italy were named after Mongol rulers, including Hulagu: names such as Can Grande ("Great Khan"), Alaone (Hulagu), Argone (Arghun), and Cassano (Ghazan) are recorded.[27]"Which reminds me of how often I see the name 'Attila' in the credit rolls of Italian television series -- another legendary hero's name (depending on one's perspective) that never lost in Italy associations of overwhelming power.

OTOH, this perhaps provided the liminal space where flourished the legendary aspects of the Oghuz and Osmans, from of whom rose the origin stories of the Ottomans, and the legendary warriors such as Ertugrul of the Kayi tribe. This season his trajectory has Ertugrul resembling both Christ and King Arthur, i.e. sharing aspects, as mythical figures invariably do.

This is the era when the Mongol conquers in Asia Minor converted to Islam, while also importing vast numbers of Chinese scholars and administrators from the Yuan dynasty back in Eastern Asia.

What these alliances did do (as with Venice) was facilitate trade routes and exchange between east and west across Asia Minor to China and back -- and across Africa too.

|

| A reading done by Ifá; versus the Dilogun, produces 256 possible combinations of symbols which define specific combinations of Odu. The Odu are indicted by throwing cowrie shells in the sand tray. |

| The I Ching advisories are found via throwing coins. |

El V studied the I Ching when he was taking Chinese classes, and of course he's studied Ifá -- which, it seems not too many, or anybody else, has done both. And now he's got me to bring him the historical trajectory of trade and conquest that made this cultural interpenetration possible. (The Yoruba have always been brilliant at taking something from another culture and transforming it to fit their own expression -- they still do it, as we see in Cuba all the time. Or here, for that matter -- Africans and African Americans are just brilliant at expression, form and style.)

History is so exciting! I think telling el Vaquero this stuff made him fall in love with all over again.

Ha! And to think this all is because I watch a Turkish telenovella. At one point a primary character is wearing a robe that I swore had Chinese designs on it. So I went looking at more history again. And by golly, that's yet another historic detail the series has right. It's always all about trade.

We've only resumed treading aloud, now that el V's back from Cuba, Barry Cunliffe's By Steppe, Desert, and Ocean: The Birth of Eurasia. The maps are brilliant. It's extra exciting when we hit sections that deal with the same peoples I've beeen watching on Qin Empire: Alliance, and Resurrection: Ertugrul, as well as in Jack Weatherford's books on the history of the Mongols.

I've been thinking about the steppes, nomads, Mongolians, China, Islam, and trade for several years now. But it's so complicated, and I have no grounding in the geography, so it's hard to grasp this.

Once again, I understand how impossible it is to deal with history without geography and vice versa. Ertugrul sends me back to both after every episode I watch, and I think I'm all the more improved because of it.

It's worse than sad though, that we, as USians and Europeans do NOT know this geography and history -- history of actual, long-standing empires that we've never even heard of. If we did have more than a passing acquaintance, at best, with these matters, maybe the world wouldn't in quite the state it is currently.

No comments:

Post a Comment