The "recreational" book I'm reading is In These Times: Living In Britain Through Napoleon's Wars 1793 - 1815 (2014) by Jenny Uglow. This book is rather disappointing. I was expecting more content rather than unattached, unconnected extended anecdote (this criticism is also leveled by British history reviewers too, I see). Extended as these anecdotes are though, they frequently leave out what

|

| British view of the XYZ Affair, notorious in the U.S., which here is portrayed as female. The line below reads: "Property Protected a la Francoise." |

the reader needs to know. I expected learn specifics about the banking and financing of this era, which includes a British banker pulling the financing together for the U.S., for the Louisiana Purchase. But this momentous event gets a couple of words at most -- and those words are unattached to anything -- in fact one would have to use cogitation to understand the man she mentions is a banker -- and I never learn the name of his bank. I also hoped to learn much more about what it cost Britain to blockade the U.S. shipping not only to their own markets but everyone else's.

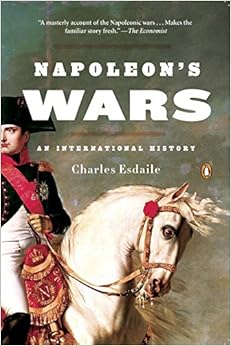

The audio book I'm working out with is Napoleon's Wars: An International History (2007) by Charles J. Esdaile. The focus isn't so much on the man and certainly not on his love affairs (yay), but on the why of the many wars he fought, and how they were won or lost and the consequences of the occurrence, the winning and / or losing, on the larger stage of Europe. Among the useful elements the author stresses is that it wasn't until the second coming of Napoleón during the Congress of Vienna in 1814 that all of Europe and Britain and were united against France. This was the only time during this entire era of warfare that happened. I hadn't quite realized that before.

|

| The first edition (1938), from Secker & Warburg |

. . . . Full of confidence these slave owners claimed 18 seats, but Mirabeau turned fiercely on them: "You claim representation preportionate to the enumber of the inhabitants. The free blacks are proprietors and tax-payers, and yet they have not been allowed to vote. And as for the slaves, either they are men or they are not; if the colonists consider them to be men, let them free them and make them electors and eligible for seats; if the contrary is the case, have we, in apportioning deputies according to the population of France, taken into consideration the number of our horses and mules?"In other words the Big Whites, the white slave owning class of San Domingo (as James refers to it, writer in English as he is), claimed population proportional representation for themselves in the Estates-General based on the number of slaves they owned (just as in the U.S. Constitution for the antebellum southern slave owning elite) -- while denying other property owners seats in the Estates-General because they were "small whites," i.e. didn't own land and slaves, the rapidly growing class of mulattoes, whose wealth in cash, land and slaves was rapidly increasing, and the "black" free people, who were not wealthy and owned no land or slaves.

The upshot was that the San Domingo Big White slave owners were allowed only 6 deputies, while:

" . . . the great Liberal orator [Mirabeau] had places the case of the Friends other Negro squarely before the whole of France in unforgettable words. The San Domingo representatives realized at last what they had done; They had tied the fortunes of San Domingo to the assembly of a people in revolution and thenceforth the history of liberty in France and of slave emancipation in San Domingo is one and indivisible."Alas, such attitude lasted for a very short time, as emancipation was not to the taste of those who initially played such a role in France in making the Revolution, the great property owner class, referred to as the Great Bourgeoisie and particularly the Maritime Bourgeoisie, whose entire fortunes were tied to every aspect of slavery in San Domingue.

This time around understand more clearly I had previously James's assertions that PM Pitt's demand to abolish the European African slave trade was high hypocrisy. By the time of the French Revolution, San Domingue was the most wealth-producing territory on the globe, financing almost all of France with its production of sugar, coffee, cotton and indigo, and the related industries including the slave trade. However, at this time as well, England's India colonies were beginning to be successful producing sugar and cotton, and the workers needed to be paid only a penny a day. San Domingue demanded more African slaves every year to put more of the island into cultivation -- devouring the captives' lives in less than ten years, from overwork, disease, starvation and abuse. By 1789 San Domingue was importing at least 40,000 Africans annually. Pitt's desire to abolish the European African trade was straight up protectionism for English products -- his definition of Adam Smith's "free market" meant eliminating the competition. Previously this had sailed right past me.

This latter, btw, is the book anyone must read before even thinking s/he's going to write anything about San Domingue, Haiti (especially if s/he's never been to Haiti, the Caribbean and doesn't know anyone from these parts of the world) or the French Revolution, whether journalism, history, literary fiction, genre fiction -- anything. For if s/he hasn't read this book s/he is going to make a huge fool of her/himself. This time around I'm reading the second edition (1963), to which James appended his seminal essay, "From Toussaint L'Overture to Fidel Castro."

Is it necessary to add that James was a Marxist in his politics and in his historical perspective? This is why U.S. history departments in the 50's and 60's didn't want him on the syllabus.

Would that all of our books would remain so foundational, so seminal, so necessary, 80 + years after initial publication as The Black Jacobins has.

Hmmm. The library says that Ancillary Sword is ready for pick-up. Will the pages of this novel contain as much excitement as the matters of these books, even though the events -- though not their consequences and effects -- took place so very long ago?. .

No comments:

Post a Comment