|

| Diana Rigg and Jeremy Brett in "Grace" - Affairs of the Heart |

The series feature fine casts of familiar players. However, though the stories are based on some of Henry James's (1843 - 1916) shorter works, the titles have the stories have been changed to female names. For example, The Aspern Papers became "Miss Tita."

As the title of the series indicates, these are all tales of love, love in all its permutations, many of which are wry, ironic and twist in directions that confound the expected romantic resolution of happy pairing. These stories are not for an audience that wants comfort romance, fast action and physical violence

The writers and director, Terrence Feeley, strip the James's stories to their bones, focusing solely upon the strange ways of men and women of a certain class all too frequently drive right past each other while desperately wished to bond. These being James works, many of them are culture clashes of how the old English monied classes and the newer American monied classes just miss each other. Everything else is told through impeccable production values of location, set dressing and particularly what the characters wear.

Which brings us to the second James, who has been featured extensively in this city's media this week, the designer, Charles James, about whom more here.

From the catalog for the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Costume Institute exhibit of Charles James:

James, who was born in England in 1906, began as a hat designer and settled permanently in the United States in 1939, building his art on the simplified lines and bias cuts of the early-20th-century French modernists Paul Poiret and Madeleine Vionnet. He also synthesized forms from the deeper past — the imposing split skirt of the 18th-century robe à la française, several kinds of bustles, army greatcoats — but his best garments exude an undeniable modernity. They are, in their own way, as organic, forward-looking and self-evident as a Brancusi sculpture, an Eero Saarinen tulip chair or a Pollock drip painting. They transcend yet celebrate function, elucidate while mystifying form, and reveal by adorning the female body in sometimes startlingly erotic terms. In the exhibition’s lavish catalog, James describes fashion as “what is rare, correctly proportioned and, though utterly discrete, libidinous.”

Similar references dot the walls of the galleries where James refers to his innovative shapes as “a high form of eroticism” and describes his driving passion “for form related to movement and, above all, to erotic grace.” He notes that bluejeans are “functional and, being functional, highly sexual” and that the true function of fashion is as “a rehearsal for propagation.” After all, what could be more crucially functional than the propagation of the species? . . . .

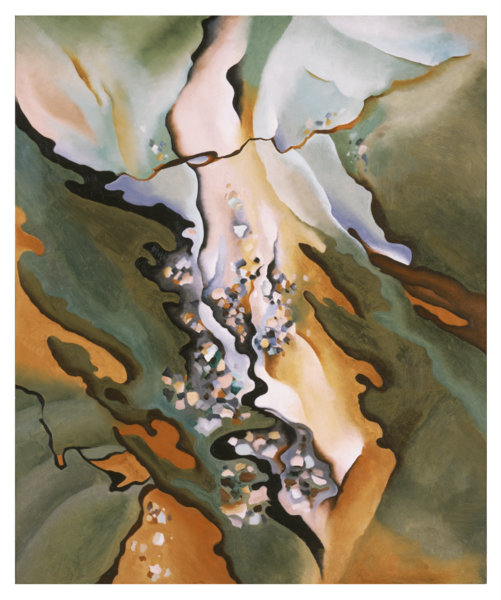

The ball gown gallery, where each dress is a feat of engineering, is one of the great demonstrations of how shape and color convey meaning and pleasure. James is at his most erotic in a 1948 ball gown partly inspired by a Georgia O’Keeffe retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in 1946.

|

"The dress is an explicit yet elegant combination of vulval drapes and labial folds in pale peach silk faille and orange silk taffeta.

|

... describes his driving passion “for form related to movement, and, above all, to erotic grace.” He notes that bluejeans are “functional and, being functional, highly sexual” and that the true function of fashion is as “a rehearsal for propagation.”This is what went through my mind last night while watching a ball room scene in one of the tales in the Affairs of the Heart.

-----------------------

* This is why too, though Henry James is an American, why so many BBC series have dramatized his fiction. In this context of love, dancing and gowns, I adore that Affairs of the Heart chose to include in the Aspern Papers in the series -- reaching as it does, back to the age that saw club-footed Lord Byron spending his time in the ballroom sneering at those who danced, while being adulated by all and sundry young ladies for his dashing poetry.

No comments:

Post a Comment