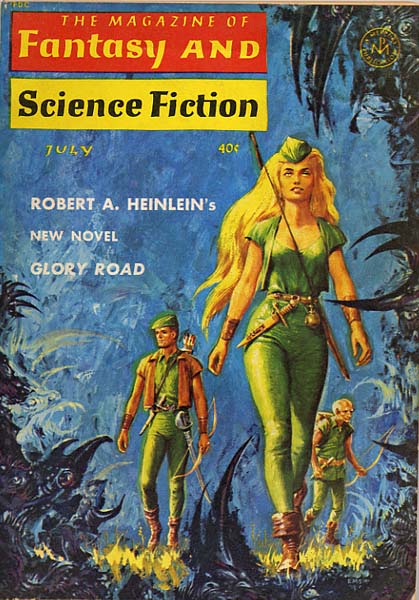

Heinlein serialized his Glory Road in the high summer of the Civil War centennial, 1963. I've often wondered whether Catton had any influence on Heinlein's choice of title for that space adventure, or in any other way.By 1963 the Civil War was branded as Catton's War as he published his second trilogy of the Civil War, called The Centennial History of the Civil War (1961 - 1965). His

books sold -- no exaggeration -- in the millions. From his first publication, he was a successful popular history writer, but his Civil War books drove his reputation up into the stratosphere. During the Civil War's Centennial Catton was on television, radio and in all the publications. At least so says the biographical materials.

I wouldn't know about that from personal experience since I too young and too far out in nowherelandia -- in a state that didn't become a state until 1889 -- for the Civil War centennial to matter or even be noticed. Settled mostly by immigrant Nordic, German, Polish and Russian farmers in the homesteading years at the end of the 19th century, there were few if any people in my my state who had a great, a grand or father who fought in the Civil War. In 1861-66 Sherman and his railway cronies hadn't even yet begun the slaughter of the great buffalo herds in my state. The gallant officers of the Lost Cause went to the Far West, like Wyoming, to reinvent themselves as stockmen/cattlemen (as Theodore Roosevelt divided owners from labor (the cowboy), or to New York, London, Chicago to become successful lawyers, bankers and investors, not as dirt farmers in the midwest. The Civil War was only talked about in the 4th grade American History class and the high school sophomore American history class.

But Catton's name as synonymous with the Civil War was so pervasive it did penetrate my consciousness a little because he was listed among the offerings from the Book of the Month Club that my grandmothers weren't interested in, and there were adverts for the books in the Sunday Minneapolis Tribune's book pages, which I would glance at without reading, while waiting for my dad to get through with the comix section. After church, while waiting for us kids and Mom to get out of Sunday School -- she was one of the Sunday School teachers -- he'd drive to town and buy the Minneapolis paper, almost only for the comix.

Whether Heinlein had any interest in the Civil War, I don't know. But Catton might have been interesting to him if only because he was such a successful writer, who served briefly in the navy during WWI, began his writing life as a journalist, who quickly became so popular and successful he was syndicated. He served as an information specialist in WWII (too old by then for active field service) and was the editor of The American Heritage Magazine until his death -- if I have that correctly. And then there was the Civil War Centennial.

I find Catton unreadable, despite all the positive remarks about him made by David Blight -- for whom I have the greatest respect. Blight admires Catton's writing style, which I find purple, mawkish and sentimental, and thus, his text, too often, ultimately dishonest.

Catton came by his fascination with the Civil War honestly, in the same way that his contemporary, Margaret Mitchell did, by listening to the veterans of the war in his small town telling each other experiences in the war, and attending gatherings of observances and pageants that were rather like early Civil War reenactments --see his memoir, Waiting for the Morning Train (1972), which is a lovely book, about an America that had long been gone for Catton too.

In some ways his first trilogy at least was a reaction to Gone With The Wind, as the war is perceived from the viewpoint of the average Union troop. But he can't resist falling for the gallant courageous knights in grey* and the glory that is war, death in service to a Greater Cause. Despite the Centennial History inclusion of social and economic causes and effects of the war, slavery, well, he's not particularly interested in it, and ultimately doesn't think the average black slave was as unhappy with his condition as northerners though. However, the war was a tragedy, in that the blood of so many gallant white people was poured into the ground in an effort that may not need to have been mobilized.

That there might some tragedy involved here for the millions of the African Americans about whose bodies everybody was fighting, including themselves to possess themselves, isn't part of his narrative. For Catton the significance of slavery and the Civil War is embodied in Abraham Lincoln, the Emancipation Proclamation and the Union's triumph, which is America's triumph of perfecting itself in its unfinished glory of its exceptionalism. What Catton thought about it can be found here.

Part of that for Catton, was that he, like most historians (did he or his academic full-time research assistant paid for by his publisher, read Kenneth Stampp's blow-up-the-paradigm, The Peculiar Institution, one wonders, published in 1956?) followed the line of definitively disproven thinking that slavery was an inefficient and economically non-productive system, which would soon have withered away, if the fire eaters on both sides, that of secession and abolition, had been effectively gotten to sit down and shut up.

Another way of putting it is that Charles Sumner got what he deserved from Preston Brooks. (Edmund Wilson certainly thought so, as we see in his Introduction to Patriotic Gore.)

Catton's vision of the Civil War is essentially Romantic, which has fully digested the Glorious Lost Cause revisionism. He cites how often Byron was found in the possession of a dead troop on both sides, and even, here we mention them, in a slave's cabin, harvested from the left behind possession of his former master, running from the Union army. In this way, I will state that Margaret Mitchell was a more honest writer than Catton: Scarlet O'Hara saw and never did see anything glorious and Romantic about the War, before, during or after. She saw it as a terrible stupid waste of time and blood, and of women's hopes and dreams.

What they had in common though, was a negative: neither of them was interested in the waste of time and blood, the hopes and dreams of African Americans.

This, while the Civil Rights movement was at its height ....

Then, there's Shelby Foote's narrative of the history of the Civil War, from the same period. Ken Burns, what you wrought was a regression yet again. But that's yet another tale.

What I really want to say, which is a caution: reading these books is still a worthwhile experience, but they should not be the first books about the Civil War one reads, because imprinting is inevitable, nor should they be the only books read about the Civil War. This holds at least as much for Foote as for Catton.

----------------

* Most of the troops in the CSA army never received a uniform and those that did hardly ever got a second one; the CSA couldn't organize itself to uniform its army. But then they were mostly poor men, who were, in the opinion of many of their planters' sons' officers, no more worthy of the respect of clothes than their slaves back on the plantation. They weren't paid or given leave, tents, blankets or food either -- just like the people back home on the plantation that the troops were bleeding for the planters' to keep possession of.

1 comment:

Terrific commentary by Blight on Edmund Wilson here. I feel a bit smug because I've figured all this out already, on mine own, in connection with Patriotic Gore, when I read it for the first time some years back, and then again, more recently, to confirm what I thought.

It rankles me immensely still that Louisa May Alcott was not included among Civil War era writers.

http://www.slate.com/articles/life/history/2012/03/edmund_wilson_s_patriotic_gore_one_of_the_most_important_and_confounding_books_ever_written_about_the_civil_war_.single.html

Post a Comment