|

| Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, self-taught scholar and poet of New Spain (Mexico). |

No longer was reading for pleasure, inspiration or information limited to academics and churchmen with access to archives and libraries, or exceedingly wealthy individuals who could patronize poets, scholars and historians, and buy expensive hand-written manuscripts and the finely crafted tomes.

Though the price remained out of reach for poor people, the rapidly expandng middle-class could easily afford books. Even those who served the middle-classes were able to acquire reading materials for fun and instruction.

Still, candles remained expensive, and so did fuel for fires. Many people's vision was too poor to read for themselves in such dim light -- and it would be only at night they could find an hour for themselves. So it was the most natural thing in the world that along with the flood of commercial reading materials came the practice of reading aloud in groups.

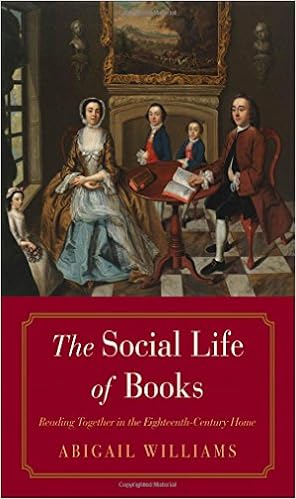

Abigail Williams has presented us with a lively account of the vastly popular activity of reading aloud in The Social Life of Books.

Williams, who teaches at Oxford University, explains that from the vantage of our own age, saturated as it is with entertainment and information, “it is hard to imagine the excitement felt by previous readers at the possibility of gaining access to a new book.”

.... In the pages of his magazine, the Spectator, Joseph Addison commanded that culture come “out of Closets and Libraries, Schools and Colleges, to dwell in Clubs and Assemblies, at Tea-Tables, and in Coffee-Houses,” and it did.Review of The Social Life of Books here.

She explains how reading became something of a “spectator sport.” Of course, as with any type of performance, one had to be properly prepared, and this led to a surge of instructional manuals, further fueling what Williams designates “the great age of elocution,” in which Britons of all backgrounds were gripped with “a near obsession with learning to read out loud.” Tradesmen formed what were rather memorably known as “spouting clubs” for aspiring public speakers, relying on such handbooks as “The New Spouter’s Companion” and “The Sentimental Spouter.” Women, who very often found themselves omitted from public performances, quickly took to them in the home, entertaining friends and family with tales and poems while they knitted or otherwise busied themselves around the hearth.

One of the reasons this reader particular enjoyed Abigail Williams study of books as a popular social activity is because it brought back vividly my first ideas of reading aloud, entertainment, instruction and novels went together naturally. It was an illustration, of a servant girl by the kitchen fire, reading aloud to the rest of the household staff, the latest installment of Samuel Richardson's Pamela: Or Virtue Rewarded.

In the Book of Knowledge's history of literature section, it was carefully explained to the young reader how important reading and novels were in instructing the poorer, less educated classes in morality and social behavior. Pamela was the paragon of virtue that all young women should model themselves on. The most important lesson of all that Pamela taught poor young girls who served in more prosperous homes that at all costs she must preserve her chastity from the household men who all would set siege to corrupt her from the paths of virtue. But if she followed Pamela's example she would not only preserve her all important good reputation -- she may well marry the son of the house and become the lady of the house, no longer a servant.

I have looked and looked in vain for an 18th century illustration that shows a young servant girl reading aloud by kitchen fire light to her gathered sister - fellow servants, but have not found one. That illustration must have been commissioned by The Book of Knowledge staff for that section.

It seems that in the 18th century when servants congregated together below stairs, out of the view of their employers, the lower household orders did nothing that interested the popular press illustrator other than drinking and generally roistering upon their masters' substance. Which reveals even more about the popularity among servants for reading aloud together 'improving' literature.

No comments:

Post a Comment