. . . . Essex Dogs (2023) by Dan Jenkins is the first in a projected trilogy set in one of my perennial eras of fascination, the 14th century. Jenkins has written many popular histories of the middle ages, many of which I've read, without being impressed; he's also written-narrated on camera quite a few history progammes for Brit tv. This is his first foray into fiction.

This first novel follows one very small troop of hired fighters -- the Essex Dogs of the title -- from the 1346 Normandy Beach landing, through this particular French campaign, to its conclusion with the Battle of Crécy. So, the part of story of King Edward III I’m interested in primarily, the role the Black Death played in the War starting in 1348 and thereafter, particularly how the English monarchy handled the effects of the Great Pestilence, is not here.

What we've got is the sort of debunking of the chivalry and prowess on the field and leadership with which we are all deeply familiar, at least in fiction, since at least the days of Glenn Cook and Abercrombie. OPn the other hand, let's be honest here: being a monarch, or merely a member of a monarch's family, is to be a monster. It cannot be helped. Part of this debunking chivalry is the theme of what a twit, turd, and creep is the Black Prince, showing him as a thoroughly horrible youth not in least above raping and further degrading peasant girls. This goes against what contemporaries and chroniclers have written of him:

"Contemporaries praised the Black Prince's chivalrous character, in particular his modesty, courage and courtesy on the battlefield. According to the medieval chronicler Jean Froissart, after the battle the Black Prince held a banquet in honour of the captured king and served him dinner.

No one can ever say that the practice of chevauchee was ever anything but brutal in the extreme, destroying everything in the path, including ethics, morals, compassion, honor and that phantasm, chivalry:

Even in his lifetime, contemporaries challenged the Black Prince’s heroic image, recasting him as a villain. Criticism focused on his chevauchée raiding expedition [-- Me here: 'raiding expedition' mildly describes the murder, pillage, rape, burning and destroying everything within as 20 mile radius of the army's passage --but never fear, the novel revels in describing these matters, in detail, as Our Dogs do indeed participate.] in France in 1355–56, a brutal affair designed to demoralise the enemy. Starting in Bordeaux in September 1355, Edward moved across France passing Toulouse, Carcassonne and Narbonne. He focused his attention on towns where he could inflict the most damage with the least resistance. His troops looted, burned property and killed inhabitants. On campaign with the Black Prince in 1355, Sir John Wingfield wrote a letter to the bishop of Winchester proclaiming that “there was never such loss nor destruction as hath been in this raid”.

This novel is as gritty as it gets, i.e. gritty for gritty's sake – how many detailed phlegm balls are hawked on every page? It was neither interesting or revelatory. It may be fiction but we’ve seen all of it depicted in novels many, many times before, and we know this first invasion of France by Edward III was successful, if only by the hair of winning at Crécy. Jones has a Name, has written many books of popular history, and television programs, but there is no fictional narrative drive, pacing or voice to this first novel by a guy who hasn’t written fiction before. On the other hand, this novel details this “road to ruin for both England and France” as The Spectator’s reviewer labeled this 1346 campaign, the initiation of what became the 100 Years War -- though truly, the war began quite a few years earlier than 1346, at least as early as the Battle of Sluys, 1340 -- or even earlier.

Jones tells us he got the idea for how the book should work from a dinner with GRRM.

It was an interesting experience though, reading the fictional Essex Dogs by night, and three times a week working out to the audio version of Ian Mortimer's Edward III: The Perfect King: The Life of Edward III, Father of the English Nation (2006). I've read biographies of Edward III by other authors, who admire him for many reasons, while providing a fair judgment of the shortcomings, or downright evils that may have been committed -- though which is which, contemporaries, posterity and historians do not necessary agree to.

Myself am suspicious of Mortimor’s claims that Edward II wasn’t executed, but lived on as a wanderer for another decade + in Europe. I also admit to being skeptical regarding Edward III's expenditures on luxuries of every kind, including dressing people for the earlier decades' endless tournies being excused as necessary PR for the Crown of England who also must project an aura as the ultimate badass warrior king, rather than as bad for England as well as for the war -- I mean the expenditure is even more astounding than the accounts of what the Queen Mother spent purely on luxurious living, decade after decade, including her racing stables -- every year Queen Elizabeth had to pay off her mother's debts. Mortimer (one wonders: distant relative of the Mortimer family who highjacked Edward II's crown?) excuses his order to behead his uncle, the Duke of Kent, as something he had no choice about – that in particular, I’m not buying, since in a matter of less than a half year Edward III and his supporters arrested Mortimer and executed him.

Alas though, this biography doesn't answer my perennial question, which is how in the world were France, particularly, and England also, keep fielding armies for this war when the Great Mortality returns time and time and time again, crops can't be planted, or if they are the English burn them or steal them so famine stalks France. Where are the fighting men coming from -- particularly when so many French nobles are killed at the same time in such military disasters as Crécy and Poitiers? The plague came back to England too, crops weren't planted and / or the weather destroyed them, yet somehow Edward III manages to keep getting ever increasing taxation passed to fund his wars, while so many die and go hungry.

The writers / historians I've read haven't mentioned the supreme irony that Edward III, the supreme King of Chivalry, identifying himself and his court with mythical King Arthur, chivalry's values, and performative, at least, practices, was the European king to dethrone the traditional aristo knight in shining armor as skilled swordsman and horse rider, by funding and encouraging in every way projectile weapons, from the long bow to gunpowder and cannon. They Do Say there were early cannon used at Crécy.

Balancing out some of the lacks as perceived in Mortimer's biography of Edward III, are his frequent citations of the rather astonishing number of successful and effective warrior noblewomen that populate the 14th century, such as Joanna of Flanders. Isabella of 15th C Spain did not come out of a vacuum.

John Sayles Delivers Epic Battles and Travels in a New Novel

“Jamie MacGillivray” gives readers a sweeping tour of 18th-century history, from Scotland to the American Colonies.

The reviews are quite good.

Then to the 19th century New York City:

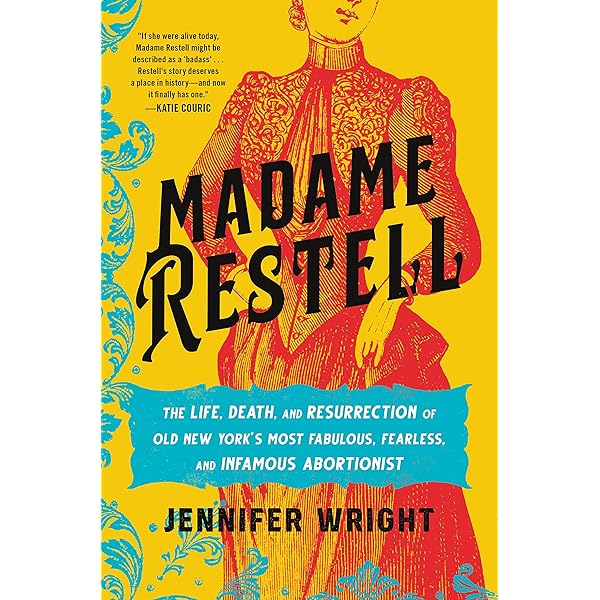

MADAME RESTELL: The Life, Death, and Resurrection of Old New York’s Most Fabulous, Fearless, and Infamous Abortionist (2023) by Jennifer Wright.

No comments:

Post a Comment