|

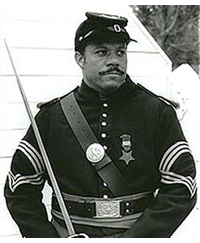

| A Union soldier, an escaped slave from Kentucky, verified Douglass' statement when he said, “When I donned my Union blues, I felt freedom in my bones” .... |

|

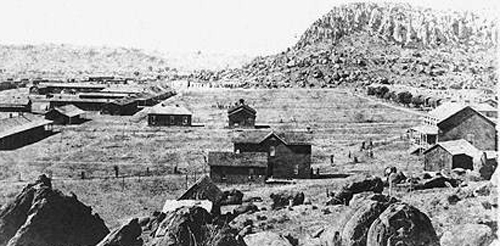

| Camp Nelson, the largest recruitment center in Kentucky for the recruitment of black soldiers in 1864. Information about Camp Nelson and its black regiments here. |

|

| There are many black Kentuckian Civil War reenactors. |

What unfolded over the next 10 months was one of the most extraordinary events of the entire Civil War. As many as 57 percent of all military-age black men in Kentucky joined the Army; nearly all of them had been slaves right up to the moment they enlisted. No other slave state witnessed such a staggering enlistment rate. Closest were Tennessee and Missouri, where 39 percent of eligible black soldiers joined. And just as white Kentuckians became increasingly disaffected with the emancipationist turn in the Civil War, black Kentuckians filled the state’s draft quota. ...

As all Kentuckians understood, black enlistment meant more than filling out the ranks of the Union Army in the war’s final, deadly months. In no other state was black enlistment more directly tied to emancipation than in Kentucky. Even as other Union slave states – Missouri, Tennessee, Arkansas and Maryland – moved to eliminate slavery in the war’s final months, Kentucky’s Unionist leaders stood firm in favor of the peculiar institution. As a result, joining the Union Army proved to be the only path to freedom for black men and for their families. More than offering mere numbers in the ranks, these black Kentucky soldiers helped transform a conservative war for the old pro-slavery Union into a revolution in behalf of a Union based on a “new birth of freedom.As we know, full emancipation did not arrive until quite some time after Lee's surrender at Appomattox. For black men, remaining in the military was the best way of ensuring their freedom would c

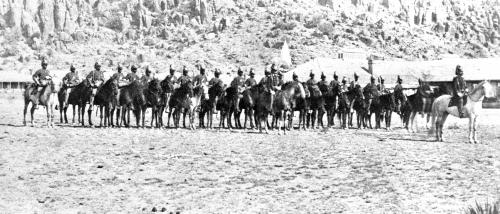

Though this Disunion column doesn't mention them, as outside the chronological purview, the Buffalo Soldiers come to mind, particularly this week, since after the war some of the most well-known black regiments were stationed at Fort Davis.

This map shows Fort Davis and the associated Davis Mountains State Park* location in northern Presidio County (the Davis Mountains are referred to, probably most often in Texas, as the Alps of Texas).

Life for African Americans remained difficult after Emancipation. Among the many towering obstacles put in the way of African Americans claiming their rightful participation in society, by the various systems, north and south, African Americans were denied employment in almost any work that would allow for, either or both, accumulation of capital and the opportunity of social and political position. The objective was to keep African Americans in the south, laboring in what became the neo-slavery of Jim Crow.

|

| Fort Davis 1885 |

|

| Fort Davis Buffalo Soldiers 1875 |

|

| Fort Davis restoration |

|

| Fort Davis National historic site |

An exception, to degree, to this system, was the military. Many African Americans preferred to stay within the army than go back to work as, say, a sharecropper. With the Civil War finished, the U.S. army could now give its attention to "subduing" the western tribes. The postings in the Southwest were fairly miserable, far from even towns, much less urban centers. The conditions were monotonous and frequently dangerous. African Americans filled the need for troops. The military provided a stable paycheck, and security from the violence of northern white supremacists, and labor coercion from southerners outraged at the idea of 'free" black men.

An account of the history of the Buffalo Soldiers at Fort Davis is here.

It also provided an opportunity to put two colonized groups of people at war with each other for the benefit of the white supremacist establishment. But yet, yes, a man has got to do what he's got to do, to support his life and his family. Most of all, it's not for someone like me to criticize such choices.

-----------------------

* Birders' Alert: The Davis Mountains State Park does weekly birding hikes in the primitive area of the park.

No comments:

Post a Comment