. . . . Coney catching is still in play, even if looking for rubes and marks on city streets isn't called that any longer.

A presentable young white man stopped me on the sidewalk Friday and asked if I spoke English. He said he couldn't tell by looking if "the people around here spoke English or not, and it seemed that hardly anybody did." Which that, right there, made my hackles raise. Why is his problem for pete's sake? Because all around us on the sidewalk were people conversing in English.

Blahblahblah, he needs to get back home to Ashville, NC, where he lives. He shows me his driver's license on top of a wad of bills that is the money to buy his ticket home. The driver's license could be him, who knows. He is $6 short of the money he needs to buy a ticket on the China Town bus that will take him to Ashville, and could I help him out, please. He's "so embarrassed and humiliated to be asking but has no choice."

I know nothing about the China Town bus except that it takes people to the casinos, the buses are poorly maintained and the drivers poorly trained and often over tired -- accidents happen a lot. Maybe it goes to Ashville, I don't know. I do know Ashville a little though. I've been there. I've spent some nights there in a very nice B&B during our southern journeys. He doesn't sound Ashville to my ears.

What I'm hearing my head is Elizabethan writer and dramatist, Robert Greene, who wrote the Cony Catching Pamphlets. They purport to describe how these London thieves and con men -- the coney catchers (various spellings; it's the 1500's) -- work on the ignorant and trusting from out of town to separate them from their money and other goods -- sometimes even their lives.

Maybe, the guy was for real? Maybe he wasn't. In case he was for real I gave him a dollar, not the 6 he asked for. He wasn't quite able to conceal his resentment that I didn't give him $6. I said, "I will be asked for money by at least 5 more people today before I go home and they'll all be visibly far worse off than you appear to be." He disappeared just like that.

As of today I'm still hearing coney catcher in my head about him.

Partly this is because about 8 days ago I had read the 4th installment in P.F. Chisholm's Sir Robert Carey historical mysteries, A Plague of Angels (1998).

This one takes place in London. One of the characters is the young William Shakespeare, during the years the theaters are closed due to plague. He's not yet Shakespeare, and almost as wet as the young Endeavour Morse -- though he will surprise the reader by the end, as well as Sir Carey, in more than one area. After all, he is still Shakespeare, whether young, unknown and not that experienced.

This portrait of young Shakespeare, in the missing years, so to speak, which are also plague years in which the theaters are closed, is unlike any fictional Shakespeare by other novelists. He’s working for Sir Carey’s father as a footman and for Kit Marlow (a nasty piece of work is Marlow) as a spy – i.e. spying on Carey’s father (his father is Queen Elizabeth's nephew and cousin, though he was illegitimate, via her sister from Henry VIII) for Vice Chamberlain, Thomas Heneage (who, like Hundson himself and Sir Robert and Shakespeare, are all real historical figures). The slim novel is very well paced, though stuffed with so much mystery, suspense, action and character in so few pages, all tied neatly together, and most satisfactorily. And, especially, this Shakespeare, and the reason for the Dark Lady sonnet with the wires out of her head – brilliant! The angels? Counterfeit Queen’s money, gold coins, and they are the roll and role of plot.

Robert Greene is also a character in Plague of Angels, so thus his Pamphlets were much in my mind, as well as Carey's Scots servants getting taken in by cony-catchers. These days among literary scholars the primary reason we are acquainted with Robert Greene at all is because of his Groats-Worth of Witte, bought with a million of Repentance, and that because it is thought to contain an attack on Shakespeare (among others; Greene was not a popular figure among his contemporaries.

Because of Chisholm's Sir Robert Carey series, I seem to have begun a project of watching -- re-watching in many cases, such as rewatching the episodes of the Tudors that include Elizabeth the child and gangly girl. -- television series and films that feature Queen Elizabeth I. Over the weekend I saw the 2005 British miniseries Elizabeth I -- not BBC (2 parts) in which Elizabeth is played by Helen Mirren. She does as splendid a job with it as one would expect. The series begins about half way through her reign and concludes with her strong intimation of coming death. Next up Cate Blanchette's two Elizabeths, followed by the 1971 Elizabeth R series in which Glenda Jackson plays her.

The one I'm looking for, and which seems hard to find is the 2005 four-part miniseries from BBC in a partnership, Elizabeth I: The Virgin Queen. This one includes Tom Hardy in the cast. This one was shown on PBS Masterpiece in the US.

So is it that at a certain stage in her career, a woman of a certain stature in her career as an actor, feels she must play Elizabeth? Or is it that others feel she must play Elizabeth? There are others I'd like to see too.

Here's a website with a list of Elizabeth-Tudor movies.

Monday, October 22, 2018

Saturday, October 13, 2018

Gilded Age: Reads That Go With the Watching

. . . . Edith Wharton’s The Buccaneers and Age of Innocence are cited frequently by British Anne De Courcey in her The Husband Hunters: American Heiresses Who Married Into the British Aristocracy (2017).

It is De Courcey's careful conversion of the obscene amounts spent by the women of this class to further their social rivalries and social climbing that is most revealing of the age. Though she doesn't dwell on this at all, this money was extracted by pillage and rapacious oppression of the laboring classes, who much of the time, due to the boom and bust US economic system, frequently were so poor they starved and froze to death on the streets outside these women's blunderbuss palaces, aimed at least as much toward the poor as at her rivals. The author's discovery that it was often the Gilded Age mothers who drove their daughters to marry into Europe's aristocracy is merely an appendage of the mothers' rivalry and climbing. Often these marriages were against what the daughters themselves may have wanted -- if, that is, they'd even been allowed in their rearing to consider themselves as a separate person at all, rather than yet another means of her mother's will.

The social world of this era was a pure matriarchy. Thus De Courcey also cites US economist Thorsten Veblen's The Theory of the Leisure Class, (1899) as to why this was so. There wasn't much in this book that I or any historian of 19th century US, or its literature, particularly after the War of the Rebellion, wouldn't be familiar with, but it is an entertaining read, and the photos De Courcey chose are excellent.

. . . . However, this book, along with the films mentioned in the previous entry, further widens and deepens the history of New York City's Gilded Age eras, along with the books discussed earlier this week by their authors at the CUNY Graduate Center:

Suspect Freedoms: The Racial and Sexual Politics of Cubanidad

in New York 1823 – 1957 by Nancy Raquel Mirabal,

and, Sugar, Cigars & Revolution: The Making of Cuban New York by Lisandro Pérez – both from NYU press.

Both authors are Cubans though they've been in the US since childhood. Lisander's an academic sociologist and Nancy's an academic historian. Lisander's and Nancy's book cover the same years, much of the same issues of Cuban independence, revolution and abolition of slavery, but they do it with different focuses.

Lisander's research is primarily on the wealthy, for whom independence at times mattered, but, like the wealthy English colonists of North America, true revolution, i.e. real change in the structures and system, and certainly abolition, were not their agenda. Nancy focuses on the poor and the Afro Cubans, and other essential parts of the Cuban revolutionary and independence clubs and movements, such as the labor movement. This contributed no little to the exciting evening of their co-presentation as they discussed and amplified each other's contributions to the subject of Cubans in New York City.

Their research into NYC and US history is massive and meticulous. But somehow they both missed the NY investment in the ship building and cargoes of the Africans brought to Cuba after the abolition of the African slave trade. Thus those very wealthy slave owning Cubans who were in New York also made connection between themselves and the wealthy Southern slave owners such as the governor of Mississippi, who wished to annex Cuba as a state, to which then, the African slave trade not allowed to the US, as protection for their slave breeding industry, they in turn could turn into a market for their overpopulation of slaves.

During the q&a an attendee asked them from where the Cuban slaves came from. In their responses about the 19th century, which only then did agricultural slavery become important in Cuba, neither mentioned the US false flag sales to many slave ships of many nationalities. As part of the Treaty of Ghent (War of 1812), one of the provisions was that the Brits, who were the ones to abolish the African slave trade, were not allowed to stop and inspect US shipping. So, naturally, the US wealthy classes from all along the coast, and New York and Boston particularly, invested heavily in building those slave ships and their cargoes.

The wealthy Cuban power elite met these US investors fairly often in New York before the Waa, surely. They did plot with Southerners who planned to filibuster Cuba -- as we describe in Slave Coast, -- and surely they invested in the slave ships too (According to the royalty checks, Slave Coast continues to sell, and by the reviews posted on amazilla, is continues to be read!).

But the authors weren't looking for this kind of information. Though they obviously know a great deal about Cuban slavery's history, that's not one of the subjects of their books, which they both worked on for years. Lisandro worked on this book for 13, and Nancy has worked on hers for over 20 years.

Also they both cite the accounts of the obscenely wealthy Cuban daughters at Saratoga (quoting, of course, Edith Wharton) as evidence of how much this class of Cubans penetrated the highest social levels of NY. But that's not exactly right. The highest class, the truly old social class of Knickerbockers, the truly exclusive society, went to Newport. They'd not be seen dead in Saratoga, NY, or Long Branch, New Jersey, where the excluded coarse 'new' plutocrats and their families, like Jay Gould -- and that coarse little man, President Grant -- vacationed in summer. -- bringing their own stock tickers, telegraph machines, and later their own telephone lines, to keep track of the markets.

One of the purposes of Newport indeed, almost created by Mrs. Astor's social arbiter, Samuel Ward McCallister, was to keep those dark Cubans and others beyond the pale of marriage away from their sons and daughters, and themselves. Both Edith Wharton and Anne De Courcey speak to this in their writing. The only acceptable marrying out of their elite of the elite sets for Astors, Schermerhorns, Schuylers, Van Rensselaers was European aristocracy, preferably British aristocracy. A title always trumped wealth and background, opened every door of inclusion. (It was permitted for the lesser families of their set to intermarry with the most powerful and elite of the Southern slaveocracy, however.)

As we too know personally these locations and these landscapes and histories of Cuba, of NYC, of the South, this event was particularly charged with pleasure in the work of these two splendid works of history.

This fall I've enjoyed the way P.F. Chisholm has put so many historical figures in her Sir Robert Carey novels, he himself also having lived and written books about his adventures. I could see doing that too with the Gilded Age. The heroic President Grant could be included -- countering the meanness with which he's been treated in fiction by Henry Adams, for instance. That would be fun.

It was a lovely night of thought and hanging out -- after I took a half THC20:1. I’d forgotten not only to put on my jewelry, but had forgotten to take vitamins and pain meds, before leaving the apartment after lunch. By 7 PM I really needed that tablet, one of which el V happened to have with him. We ended up having dinner in the grad center area, at a classic Irish pub, with classic Irish pub food and classic undocumented young, pretty Irish wait girls. I suddenly peaked from the tab about the time our plates arrived. For about ten minutes there was absolutely no pain of any kind. physical or emotional, just this enormous sense of release and well being. I'd never taken one of those tabs -- and here I had taken a whole one!

OK. Now I know how this works. Definitely taking some these with me on the January bus trip in Eastern Cuba.

It is De Courcey's careful conversion of the obscene amounts spent by the women of this class to further their social rivalries and social climbing that is most revealing of the age. Though she doesn't dwell on this at all, this money was extracted by pillage and rapacious oppression of the laboring classes, who much of the time, due to the boom and bust US economic system, frequently were so poor they starved and froze to death on the streets outside these women's blunderbuss palaces, aimed at least as much toward the poor as at her rivals. The author's discovery that it was often the Gilded Age mothers who drove their daughters to marry into Europe's aristocracy is merely an appendage of the mothers' rivalry and climbing. Often these marriages were against what the daughters themselves may have wanted -- if, that is, they'd even been allowed in their rearing to consider themselves as a separate person at all, rather than yet another means of her mother's will.

The social world of this era was a pure matriarchy. Thus De Courcey also cites US economist Thorsten Veblen's The Theory of the Leisure Class, (1899) as to why this was so. There wasn't much in this book that I or any historian of 19th century US, or its literature, particularly after the War of the Rebellion, wouldn't be familiar with, but it is an entertaining read, and the photos De Courcey chose are excellent.

. . . . However, this book, along with the films mentioned in the previous entry, further widens and deepens the history of New York City's Gilded Age eras, along with the books discussed earlier this week by their authors at the CUNY Graduate Center:

|

Suspect Freedoms: The Racial and Sexual Politics of Cubanidad

in New York 1823 – 1957 by Nancy Raquel Mirabal,

and, Sugar, Cigars & Revolution: The Making of Cuban New York by Lisandro Pérez – both from NYU press.

Both authors are Cubans though they've been in the US since childhood. Lisander's an academic sociologist and Nancy's an academic historian. Lisander's and Nancy's book cover the same years, much of the same issues of Cuban independence, revolution and abolition of slavery, but they do it with different focuses.

Lisander's research is primarily on the wealthy, for whom independence at times mattered, but, like the wealthy English colonists of North America, true revolution, i.e. real change in the structures and system, and certainly abolition, were not their agenda. Nancy focuses on the poor and the Afro Cubans, and other essential parts of the Cuban revolutionary and independence clubs and movements, such as the labor movement. This contributed no little to the exciting evening of their co-presentation as they discussed and amplified each other's contributions to the subject of Cubans in New York City.

Their research into NYC and US history is massive and meticulous. But somehow they both missed the NY investment in the ship building and cargoes of the Africans brought to Cuba after the abolition of the African slave trade. Thus those very wealthy slave owning Cubans who were in New York also made connection between themselves and the wealthy Southern slave owners such as the governor of Mississippi, who wished to annex Cuba as a state, to which then, the African slave trade not allowed to the US, as protection for their slave breeding industry, they in turn could turn into a market for their overpopulation of slaves.

During the q&a an attendee asked them from where the Cuban slaves came from. In their responses about the 19th century, which only then did agricultural slavery become important in Cuba, neither mentioned the US false flag sales to many slave ships of many nationalities. As part of the Treaty of Ghent (War of 1812), one of the provisions was that the Brits, who were the ones to abolish the African slave trade, were not allowed to stop and inspect US shipping. So, naturally, the US wealthy classes from all along the coast, and New York and Boston particularly, invested heavily in building those slave ships and their cargoes.

The wealthy Cuban power elite met these US investors fairly often in New York before the Waa, surely. They did plot with Southerners who planned to filibuster Cuba -- as we describe in Slave Coast, -- and surely they invested in the slave ships too (According to the royalty checks, Slave Coast continues to sell, and by the reviews posted on amazilla, is continues to be read!).

But the authors weren't looking for this kind of information. Though they obviously know a great deal about Cuban slavery's history, that's not one of the subjects of their books, which they both worked on for years. Lisandro worked on this book for 13, and Nancy has worked on hers for over 20 years.

Also they both cite the accounts of the obscenely wealthy Cuban daughters at Saratoga (quoting, of course, Edith Wharton) as evidence of how much this class of Cubans penetrated the highest social levels of NY. But that's not exactly right. The highest class, the truly old social class of Knickerbockers, the truly exclusive society, went to Newport. They'd not be seen dead in Saratoga, NY, or Long Branch, New Jersey, where the excluded coarse 'new' plutocrats and their families, like Jay Gould -- and that coarse little man, President Grant -- vacationed in summer. -- bringing their own stock tickers, telegraph machines, and later their own telephone lines, to keep track of the markets.

One of the purposes of Newport indeed, almost created by Mrs. Astor's social arbiter, Samuel Ward McCallister, was to keep those dark Cubans and others beyond the pale of marriage away from their sons and daughters, and themselves. Both Edith Wharton and Anne De Courcey speak to this in their writing. The only acceptable marrying out of their elite of the elite sets for Astors, Schermerhorns, Schuylers, Van Rensselaers was European aristocracy, preferably British aristocracy. A title always trumped wealth and background, opened every door of inclusion. (It was permitted for the lesser families of their set to intermarry with the most powerful and elite of the Southern slaveocracy, however.)

As we too know personally these locations and these landscapes and histories of Cuba, of NYC, of the South, this event was particularly charged with pleasure in the work of these two splendid works of history.

This fall I've enjoyed the way P.F. Chisholm has put so many historical figures in her Sir Robert Carey novels, he himself also having lived and written books about his adventures. I could see doing that too with the Gilded Age. The heroic President Grant could be included -- countering the meanness with which he's been treated in fiction by Henry Adams, for instance. That would be fun.

It was a lovely night of thought and hanging out -- after I took a half THC20:1. I’d forgotten not only to put on my jewelry, but had forgotten to take vitamins and pain meds, before leaving the apartment after lunch. By 7 PM I really needed that tablet, one of which el V happened to have with him. We ended up having dinner in the grad center area, at a classic Irish pub, with classic Irish pub food and classic undocumented young, pretty Irish wait girls. I suddenly peaked from the tab about the time our plates arrived. For about ten minutes there was absolutely no pain of any kind. physical or emotional, just this enormous sense of release and well being. I'd never taken one of those tabs -- and here I had taken a whole one!

OK. Now I know how this works. Definitely taking some these with me on the January bus trip in Eastern Cuba.

Labels:

books,

Cuba,

Cuba history,

historical fiction,

NYC,

us history,

Women,

writers

Tuesday, October 9, 2018

Colette (2018)

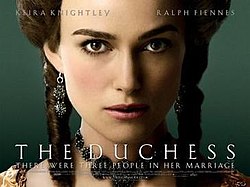

. . . . Keira Knightly as the title figure and Dominic West as Willy, with other recognizable Brit television actors in secondary and supporting roles.

Colette's an old-fashioned period piece Hollywood big movie featuring two internationally recognizable faces, playing recognizable celebrity faces of the time, expensive, slick and glossy.

Emphasis on celebrity. The author and her husband, and the infamous Claudine books (1900 - 1904) she ghost wrote and Willy took the credit for (and all the very significant profits, which he threw away profligately on race horses, the gambling tables, wine, women and song), were indeed all the rage when they came out. Yet these celebrity sequences seem more like now than then, yah?

As usual with historical drama, it's rather too clean and flat in panorama, mise-en-scène and close-up to be convincing (no broken down horses pulling public hacks, no manure in the streets, no bad teeth). As Colette and Willy are writers, and writing is not a dramatic moving, action act, we have lots of tasteful noisy sex instead.

This viewer found the all-British cast and production hilarious, as everyone speaks in posh Brit English, but, when they write, we’re shown French pouring out of the nib, voiced-over in the posh English.

Further hilarity ensues due to Dominic West as Willy, who is best known for playing Usian Baltimore detective cad-to-women, McNulty, on The Wire, and lately, for at least 4 seasons, the Usian novelist cad-to-women, Noah Soloway, on The Affair. Another point of hilarity is the current Poldark’s Demelza’s actor, Eleanor Tomlinson, playing bisexual sex scenes, in one of the worst so-called Southern accents evah – she’s supposed to be from New Orleans. Brit actors always murder Southern accents, seemingly not even understanding that there are very many different Southern ways of speaking. (Personal unpopular opinion -- Tomlinson's Demelza annoys the heck outta me. So far there's been no indication that Tomilinson can act, whether in period Agatha Christie's Ordeal By Innocence (2018), or on Poldark or in Colette.)

Points in favor of the flick: if not provocative of thought, it's gorgeous to look at; Knightly impresses with her non-body double or stand-in lengthy action scenes that involve a variety out of the standard repertoire of theatrical skills, from miming to dancing; Knightly is more convincing -- despite not being believable for a second as a 17-year-old - as a fin de siècle, Gilded Age figure than she was as the Georgian era title character, in The Duchess.

....(Colette eventually goes on the stage after leaving Willy, traveling music halls and theater throughout France, many of them ramshackle and many a gig that doesn't pay much more than for wine and cheese. This is part of her biography, but the film makes it look far less grueling and impoverished than Colette's own testimony, and those of others, inform us.)

.... (Knightly was as wrongly cast for that one as Winona Ryder was in Scorsese's Age of Innocence, her Gilded Age flick -- though Michelle Pfeiffer was perfect as the USian Polish Countess-by-marriage -- Knightly even looks like Winona Ryder in this. Her body type did not conform in any way to the fashions as they were, nor did her body language, just as Ryder's did not.)

Colette’s life in truth was messy, unlike this adult coloring book of luxe La Belle Époque France movie, which is splashed as “true feminist story!” Nor was Colette particularly feminist. So much of her fiction, despite the bisexual frissons, was about women victimized by, sighing, dying for love – love of a male cad.

... (Her Chéri novels were a refreshing exception to that, as it is the young lover infatuated with an aging, retired courtesan is the one who dies for his love. The 2009 film, Chéri, centering one of my favorite to watch actors, Michelle Pfeiffer as Lea, the exquisite, retired courtesan from the days of les grandes horizontals, whom Chéri cannot grow beyond, is exquisite in all the right ways, faithful in tone and attitude to the novels.)

It was a holiday yesterday, but still the theater held a respectable number of audience members. The variety of the audience was interesting: lesbian couples of various age cohorts; young hetero couples (one of whose male half kept getting up and coming back, disturbing everybody in lumbering oafish style for extended periods of time going and coming -- even clanging metal -- what? ); and a surprising number of young male-male couples, though these I had no way of knowing whether they were gay or not, and single young fellows.

The conversation in the line for the ladies room after the showing was disheartening due to the enormous amount of misinformation being bandied about as fact about Colette and her work. I seem to have been the only one there possessing solid grounding in her life and the period she lived in, and the only person who had actually read her work.

A last point of hilarity: in the ladies room line, it was being repeated from the closing epilogue text verbatim, that "Colette was the most important woman writer in France. She changed fiction forever."

I kept hearing Simone de Beauvoir's outrage. I recalled her gleeful, merciless dissection of Colette's helpless, hapless feminine dependency on having the love of a man, of being in love, in order to have meaning, significance and identity, especially in The Second Sex (1949). This, though in many ways, hilariously, hers and Colette's novels have much more in common in this area than Beauvoir herself realized: so much doomed love, clothes making the woman, intellectual and creative and sexual rivalries as they contain. The difference though, is that Beauvoir’s stand-in in her autobiographical novel, She Came To Stay (1943), Françoise, literally, with her own hands, kills off her rival for Pierre’s devotion. Perhaps Beauvoir believed Colette earned her condemnation by being too femininely weak to do the same . . . . Actually, She Came to Stay is period novel I'd love to see turned into a film.

Colette's an old-fashioned period piece Hollywood big movie featuring two internationally recognizable faces, playing recognizable celebrity faces of the time, expensive, slick and glossy.

Emphasis on celebrity. The author and her husband, and the infamous Claudine books (1900 - 1904) she ghost wrote and Willy took the credit for (and all the very significant profits, which he threw away profligately on race horses, the gambling tables, wine, women and song), were indeed all the rage when they came out. Yet these celebrity sequences seem more like now than then, yah?

As usual with historical drama, it's rather too clean and flat in panorama, mise-en-scène and close-up to be convincing (no broken down horses pulling public hacks, no manure in the streets, no bad teeth). As Colette and Willy are writers, and writing is not a dramatic moving, action act, we have lots of tasteful noisy sex instead.

This viewer found the all-British cast and production hilarious, as everyone speaks in posh Brit English, but, when they write, we’re shown French pouring out of the nib, voiced-over in the posh English.

Further hilarity ensues due to Dominic West as Willy, who is best known for playing Usian Baltimore detective cad-to-women, McNulty, on The Wire, and lately, for at least 4 seasons, the Usian novelist cad-to-women, Noah Soloway, on The Affair. Another point of hilarity is the current Poldark’s Demelza’s actor, Eleanor Tomlinson, playing bisexual sex scenes, in one of the worst so-called Southern accents evah – she’s supposed to be from New Orleans. Brit actors always murder Southern accents, seemingly not even understanding that there are very many different Southern ways of speaking. (Personal unpopular opinion -- Tomlinson's Demelza annoys the heck outta me. So far there's been no indication that Tomilinson can act, whether in period Agatha Christie's Ordeal By Innocence (2018), or on Poldark or in Colette.)

Points in favor of the flick: if not provocative of thought, it's gorgeous to look at; Knightly impresses with her non-body double or stand-in lengthy action scenes that involve a variety out of the standard repertoire of theatrical skills, from miming to dancing; Knightly is more convincing -- despite not being believable for a second as a 17-year-old - as a fin de siècle, Gilded Age figure than she was as the Georgian era title character, in The Duchess.

....(Colette eventually goes on the stage after leaving Willy, traveling music halls and theater throughout France, many of them ramshackle and many a gig that doesn't pay much more than for wine and cheese. This is part of her biography, but the film makes it look far less grueling and impoverished than Colette's own testimony, and those of others, inform us.)

.... (Knightly was as wrongly cast for that one as Winona Ryder was in Scorsese's Age of Innocence, her Gilded Age flick -- though Michelle Pfeiffer was perfect as the USian Polish Countess-by-marriage -- Knightly even looks like Winona Ryder in this. Her body type did not conform in any way to the fashions as they were, nor did her body language, just as Ryder's did not.)

|

| (2008) |

|

| Michelle Pfeiffer, Daniel Day Lewis, Age of Innocence (1993) |

Colette’s life in truth was messy, unlike this adult coloring book of luxe La Belle Époque France movie, which is splashed as “true feminist story!” Nor was Colette particularly feminist. So much of her fiction, despite the bisexual frissons, was about women victimized by, sighing, dying for love – love of a male cad.

... (Her Chéri novels were a refreshing exception to that, as it is the young lover infatuated with an aging, retired courtesan is the one who dies for his love. The 2009 film, Chéri, centering one of my favorite to watch actors, Michelle Pfeiffer as Lea, the exquisite, retired courtesan from the days of les grandes horizontals, whom Chéri cannot grow beyond, is exquisite in all the right ways, faithful in tone and attitude to the novels.)

|

| MIchelle Pfeiffer as Lea, Chéri, 2008 |

It was a holiday yesterday, but still the theater held a respectable number of audience members. The variety of the audience was interesting: lesbian couples of various age cohorts; young hetero couples (one of whose male half kept getting up and coming back, disturbing everybody in lumbering oafish style for extended periods of time going and coming -- even clanging metal -- what? ); and a surprising number of young male-male couples, though these I had no way of knowing whether they were gay or not, and single young fellows.

The conversation in the line for the ladies room after the showing was disheartening due to the enormous amount of misinformation being bandied about as fact about Colette and her work. I seem to have been the only one there possessing solid grounding in her life and the period she lived in, and the only person who had actually read her work.

A last point of hilarity: in the ladies room line, it was being repeated from the closing epilogue text verbatim, that "Colette was the most important woman writer in France. She changed fiction forever."

|

| This book, this edition, is still on my shelves. |

|

| This book is still on my shelves too. I re-read it again, just last year. |

I kept hearing Simone de Beauvoir's outrage. I recalled her gleeful, merciless dissection of Colette's helpless, hapless feminine dependency on having the love of a man, of being in love, in order to have meaning, significance and identity, especially in The Second Sex (1949). This, though in many ways, hilariously, hers and Colette's novels have much more in common in this area than Beauvoir herself realized: so much doomed love, clothes making the woman, intellectual and creative and sexual rivalries as they contain. The difference though, is that Beauvoir’s stand-in in her autobiographical novel, She Came To Stay (1943), Françoise, literally, with her own hands, kills off her rival for Pierre’s devotion. Perhaps Beauvoir believed Colette earned her condemnation by being too femininely weak to do the same . . . . Actually, She Came to Stay is period novel I'd love to see turned into a film.

Labels:

books,

fiction,

French culture,

french history,

historical fiction,

Movies,

Television,

Women,

writers,

Writing

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)