The historical fictions first . . . .

Martha Conway. (2017) The Underground River. Touchstone, New York.

Set on the Ohio, 1838, in a Floating Theater, featuring a seamstress, who finds herself by helping enslaved people escape from Kentucky to Ohio. The problem, however, is this is 1838, deep into the Panic of 1837. Van Buren is POTUS, inheriting the consequences of Andrew Jackson’s ignorant, thus destructive economic policies, which the concentrically related conditions he created plunged the USA into the deepest and longest economic depression in the constant cycle of boom and bust economy of the country until the Great Depression of 1930’s. By 1837 - 38, businesses of all kinds, great and small, in the US and abroad, particularly England, from banks to leather shops are failing and have failed everywhere. There is no, none, nada, credit to be had by anyone, except the very few richest individuals in the country.

So then this reader cannot help wondering how these poor people along the Ohio River between Kentucky and Ohio find the bit of coin to pay admission to the Floating Theater, which isn't even a steamboat, but a barge? How in the world does the Floating Theater on such margins already, keep going?

From the Ohio History Connection --

. . . . In Ohio, many people lost their entire life savings as banks closed. Stores refused to accept currency in payment of debts, as numerous banks printed unsecured (backed by neither gold nor silver) money. Some Ohioans printed their own money, hoping business owners would accept it. Thousands of workers lost their jobs, and many businesses reduced other workers' wages. It took until 1843 before the United States' economy truly began to recover. . . .IOW, the author did a lot of research into many areas, which show up delightfully in her pages, but missing are the economic milieu of the period, which should be crucial to the story she wants to tell -- slavery is always about economics.

This is too bad for this reader, let me emphasize, as everyone else who has read and reviewed this novel appear to have never even heard of the Panic of 1837. But for this reader, this knowledge flowed constantly into the story, creating a great deal of interrogation of character and storylines. The book's characters are for the most part are interesting and vivid. But this lack of inclusion in the story of this crucial event of the 1830's and 1840's showed equally vividly the author's contrivances, which resulted in a sense of the plot becoming almost glib and as nearly as flimsy as the scenery of the plays presented by the Floating Theater.

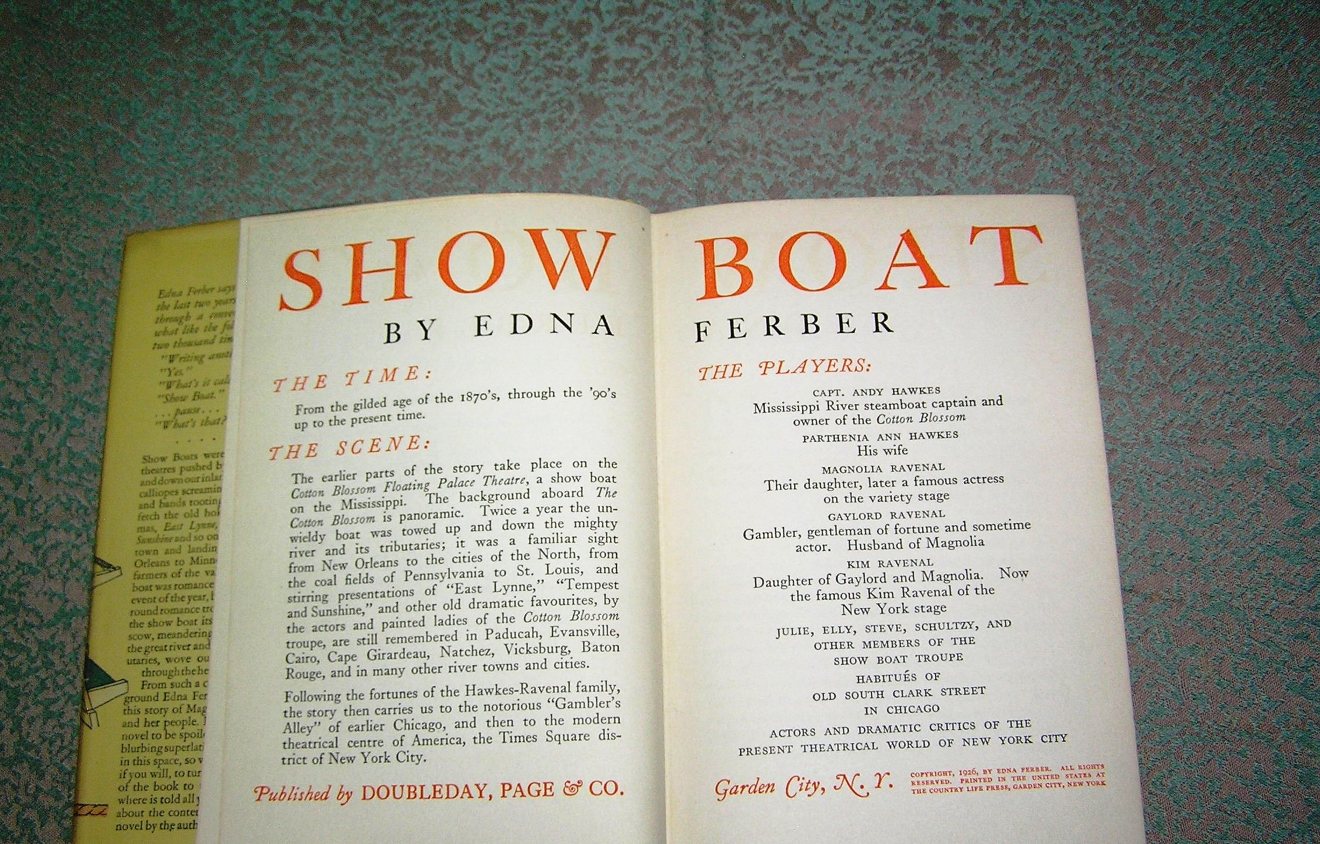

It also got this reader recollecting Edna Ferber's Showboat (1926). which was anything but flimsy. It is set during in the post-bellum era of the Gilded Age. Every shiver in the economy, every part of racism, affects the people working on the floating theater steam boat, The Cottonblossom, over the three generations of the characters in this substantial work of historical fiction.

Linnea Hartsuyker. (2017) The Half-Drowned King. HarperCollins, NY.

Cold climate fiction 9th century Norway, which this reader looked forward to, as the perfect book for that very hot, polluted and humid first week of August.

Enthusiastically positive review in the historical fiction sections. Multiple foreign rights sales.

This is first of a trilogy set in the same sort of chronotype as Nicola Griffith’s Hild. This is the author's first novel since retiring from tech and achieving an MFA from NYU, thus the author isn't yet as skilled as Griffith. The first sections are somewhat muddy slogging, as the reader attempts to locate where, when and why. This is made more confusing by sudden switches in protagonists and their limited 3rd person point of view. The novel improves about half way through, just about where this reader was going to jettison it.

The novel's titles are different in different countries. Seeing the title for the Dutch version perhaps explains some of my initial difficulties with the novel, trying to figure out who and what it was about. We open with the brother, Ragnvald, so one tends to think he’s the ‘real’ protagonist (and nothing changes one’s mind about that as the book progresses). But the sister, Svanhilde, gets pov as well -- except when they are in scenes together we get them from his pov. But the title in Dutch is De Legende Van Swanhilde -- so is Svanhilde the actual protagonist?

I’m guessing at least one of these two siblings will be in Iceland in the second volume.

Sarah Perry. (2016) The Essex Serpent. Serpents Tail – UK / HarperCollins, NY.

Set between January through November in a single year of the late Victorian era, this is a 'literary' historical fiction, which received glowing reviews in all the venues that review such fiction. For this reader though, the various parts do not connect thematically, and did not meld via the laborious and labored metaphor of the serpent of the title. This serpent writhes throughout the text in the guise of several visions: prehistoric, i.e. scientific of the real, material world, superstition of the infernal, mystical vision of the divine, creative impetus of the imagine. These and more meanings of the serpent cycles into the consciousness periodically of the people who live in a village upon the Blackwater River in Essex, close to the sea.

For someone who has read enormously in the great century of Victorian fiction, the characters felt as lesser shadows of all the Victorian characters we already know -- particularly those out of historical fiction -- rather than original figures in their own right. Except they are given to thinking as if they are no different from thos who in the 21st century, which is how the author has taken pains to tell her readers they are not. There is an exception of one of the peripherals, Naomi Banks, a motherless child with a hard drinking fisherman father. It's her story that is the interesting one, but we don't get much.

This reader got very impatient before the end arrived. The book felt about 60 pages too long, and it felt as though nothing amounted to much at all -- which is perhaps where it is like so many people alive today?

Contemporary fiction . . .

Don Winslow. (2017) The Force. HarperCollins, New York.

Police thriller suspense in New York City, glowing reviews, hailed frequently as "the perfect beach read." This reader naturally then expected it to be perfect for hot humid summer nights, of which this month there have been many (with respites, thank goodness!)

But what it did it feel like was one of those grey and dreary, interspersed with violence of weenie-wag over testosteroned New York City types from the later part of the second decade of the 21st century. However, the protag keeps telling us we're on the mean streets of present day NYC, though, naturally, mostly we're in the supposedly still Fort Apache neighborhoods of uptown baby and the 'jects and kingpin drug dealers of heroin . . . .

Narrated from the strictly limited point of view of the leader of the narcotics special forces protagonist, it sounds like something written no later than the last decades of the 20th century, with that hardboiled consciousness and narrative tone that was common for such fictions. Never fear, however, the pages are well laced with whinings about how unfairly the cops are regarded and treated by those they keep safe -- while they, particularly the protag -- committing one hideous crime after another from stealing and dealing and getting big moola by selling the drugs they take from the criminals -- not to mention spending sprees with the most expensive hookers going, and other infidelities to wives and families who are too protected and selfish to understand their special pressures.

This reader did not like this book, so skimmed from the middle to the end. At least protag dies. He dies, moaning, "All he ever wanted to be was a good cop."

Julia Glass. (2017) A House Among the Trees. Pantheon – Penguin USA / Random House. New York.

Ta -Dah!

This one is by far the winner of this reader's August's fiction reading. Despite the NY Times's snarky review by David Levitt, this reader gobbled Glass's novel down in two long nights of reading, from first word to the last word. Levitt does concede that though he despised the novel yet it was pleasing enough that one reads happily to the end -- and yes, not only does this novel provide a happy ending, but it provides several happy endings, all skillfully and plausibly wrapped together, rising out of who the multiple characters are.

Other reviewers have observed that if one likes Australian novelist, Liane Moriarty's books, and I do (the recent HBO series, Big Little Lies, was adapted to Malibu from one of her books) one might well like this novel too. But ultimately this reader doesn't see that they have much in common. For one thing, it's about the world of children's publishing. But Glass gets in so many threads of our current entertainment media, including computer games, movies and television, biking, and even museums.

It was almost like having another of Sue Miller’s splendid novels from the 90’s, (her first novel, The Good Mother, was published in 1986) when she was at the top of her form. Miller's the more graceful writer by several percentage points, but Glass's novel moves even more effortlessly than Miller's, which means I shall look out for Glass's previous novels.

Will I get in another novel before August melts into September and the fall's crazy schedule, including traveling to Cuba and to Mexico, kicks in? These last few weeks, as hot and unpleasant in some ways as they've been, have been the most relaxing I've experienced in years. It's kind of like being on vacation. Books are good for that too.

No comments:

Post a Comment